Fair Youth Beneath the Trees: Remembering Chinmoy Pramanik – Johny ML ”Then the sun cleared the hillock in a hurry, the warmth discovering

”Then the sun cleared the hillock in a hurry, the warmth discovering

him, the light dissuading him. But his calm, dark eyes sparkled as he

summoned the neutral witness of time to pay attention to his last act as

Gangiri Bhadra.”

– Shoes of the Dead (Kota Neelima)

Chinmoy Pramanik was not Gangiri Bhadra, the

protagonist of Kota Neelima’s well researched novel based

on the farmer’s suicide in India. But somehow, his untimely

demise brings the memories of Gangiri’s death. Gangiri

fought for the rights of the farmers, whose deaths were

written off as ‘natural’ ones. He had to sacrifice the welfare of

his dead brother’s family and his own security for this fight.

Finally, he too consumes pesticide and dies converting the

village moneylenders and power mongers, in the process, to

a new religion called humanity. Chinmay Pramanik did not

commit suicide. He was undergoing treatment for leukaemia

and when he passed away he was just thirty five years old.

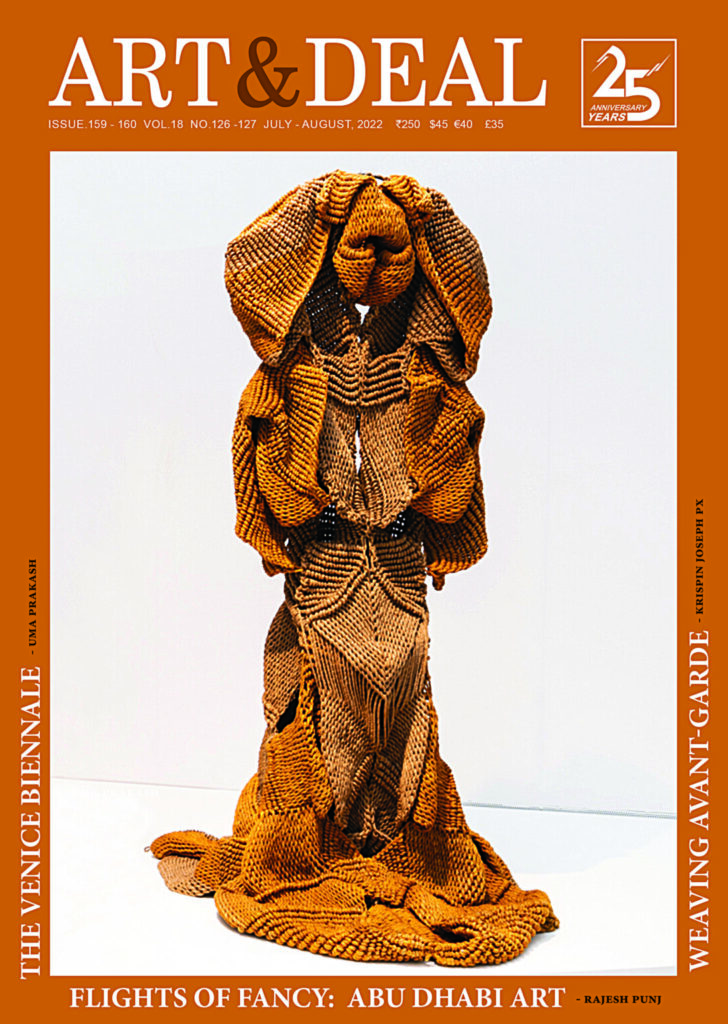

He was a talented sculptor; one of the few artists in India

who were unaffected by the illness of the market boom.

As Kota Neelima observes in another part of her novel,

an obituary means nothing. It does not say anything. The

words remain hollow and the emotions drained. The death of

a fellow being induces some kind of silence in us. We behave

like rudalis. I could have avoided writing an obituary. But it

is the curse of being a writer. I do not have any other device

to show my grief. Hence, this obituary is an effort to look

into the hollowness of my own words. Arundhati Roy, in her

God of Small Things says that when a person dies, he leaves a

hollow in the space in his own shape. I could see a tall, thin

and smiling hollowness in the air; a smile seen through the

thick beard comes out from that hollow reminding me of the

Cheshire cat, but devoid of its cynicism.

I remember meeting him last at the Space Studio in

Baroda. I had met him several times before that. Head hunters

from the art scene had gone all over the place to track down

unsuspecting but eager young artists and make them cannon

fodders for the machine called the art market. I heard his

name for the first time from one such head hunter. I saw

his works. Then I met him. He was a man with minimum

words and a lot of smiles. His works were made out of small,

carefully crafted wooden chips. Together they made a form,

most of which looked like absent figures trying to manifest

in the present. For those critics and curators who were the

propagators of new urbanism and urbanology, his works

were critiques of urban growth.

What I think today is something different. His works

always grew vertically with a ridge running through its

body. At Chintan Upadhyay’s now disputed Juhu apartment

in Mumbai, he had kept one of Chinmoy’s work, in the

drawing room. During each visit, I saw this work moved

from one place to another; sometimes to his study room

and sometimes to the bed room. The work stood silently,

vertically, like a mummified form, imparting no terror but

setting the visitor in a thinking mode. Chintan was behaving

like a museum curator, never satisfied with the placement of

the work. I remember touching the work and feeling the ups