Everyday Lifeworlds of Paintings: Possibilities of Materialist Histories-Prasanta Ray, Hyphen, Kolkata, 2024 by Anuradha Roy

The book Everyday Lifeworlds of Paintings is about complex relations between the painter and the elite patrons above him, and also between the painter and his assistants, apprentices and art material providers (i.e. people who collect, preserve, process and distribute art materials) below him. Such relations were true at least till industrially produced and commercially distributed art materials became available to Indian painters and gradually a big market was formed not only for art materials but also for paintings. To my mind, the key concern of the book is the anonymous art material-providers called ‘subalterns’ by the author. They used their local knowledge, raw imagination and physical energy to perform their task, which in many cases required quite some expertise, and often forced them to come into contact with poisonous elements of nature, and thus take considerable risk. Yet these people always remained unrecognized and unrecorded. The book is about the denials they suffered, in terms of both money and dignity. But of course, it is a fact that among the subalterns there were many apprentices awaiting promotion to the respectable artist status and some of them were sons or other blood relations of the master artists. It is also a fact that in the ecosystem of the art world, even artists in many cases share the same fate of denial and indignity; and the author addresses the artists’ subalternity too. Indeed, until and unless the category of artist gets separated from that of artisan, people creating art cannot expect their due. And there is no clear answer to the question – ‘what distinguishes an artist from an artisan?’

The book is a materialist analysis of painting as a collective performance and a layered world involving human relationships. Art history has so far paid attention mainly to aesthetics – styles and meanings of paintings, that is, to the images themselves. Though there are some good discussions of Indian painting relating it to imperialism, westernization and nationalism (exemplified by the works of Natasha Eaton, Partha Mitter and Tapati Guha-Thakurta), the social history of art has generally neglected the subaltern accessory-providers, men and women and maybe even children, operating on the fringes of artistic practices.

Denial in the case of women can perhaps be explained in terms of gender, but on the whole, this injustice surely calls for a broader and deeper exploration. However, searching for data in the face of a long history of inattention is not easy. The author strains hard to hear whispers in this world of silence. He takes a pluri-disciplinary approach freely moving across different time periods and different political economies from the prehistoric to colonial capitalism, extensively covering West Europe, India and Bengal, though the focus remains on India and Bengal. He has used all sorts of data – paintings, narratives on paintings, artists’ personal histories and autobiographical writings, artists’ manuals, art material suppliers’ catalogues, census, auction records etc. – in his search. I find the footnotes and bibliography, comprising both quantitative and qualitative materials very impressive. Not only the artistic side but also the science of colour-making has been engaged with. Techniques of painting have sometimes been discussed in detail to show how painting requires close collaboration between the artist and the art-material providers. It is very likely that the painter had to explain to the providers the meaning of a colour that he would like to use, and perhaps the latter also provided clues to the painter. At least, both had to be conversant with each other’s language. The material-provider’s was not a mechanical job.

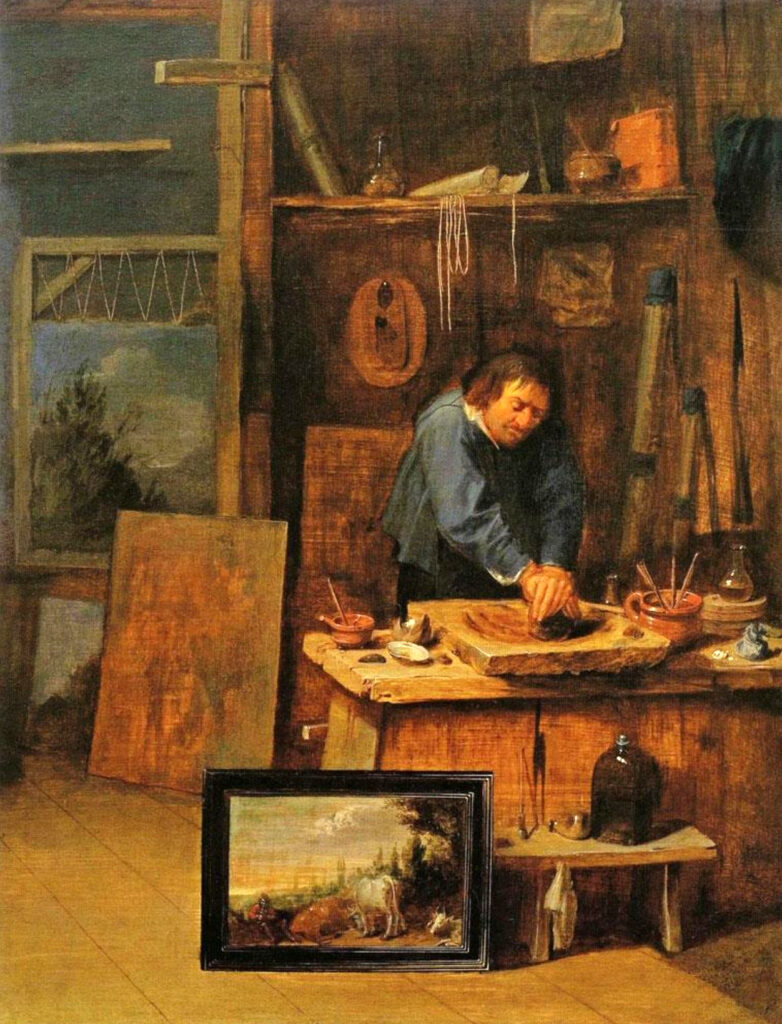

The neglect of subalterns not only in the history of art but in artistic practices themselves can be dated far back in history. The artists rarely depict subalterns, leave aside subalterns associated with their own activities. Sometimes, though, we find sketches or paintings depicting busy art studios showing assistants preparing pigments or carrying panels of wood. But these are found mostly in Europe. In India, shastric sutras were perhaps largely responsible for this neglect. Vatsayana provided recipes for preparing plaster, binding media, crayons and brushes, but did not acknowledge their critical value. Chitrasutras in The Vishnudharmattora enunciated canons for painters (e.g. the canon of proportion of the human body). The section Varnikabhangam in this text advised artists on the use of brush and colours, but it was at the bottom of the list of sadanga, the legendary six limbs of painting. Just as the shudras were born from the feet of the Purusha in a hierarchical social order, art materials were the least important in the hierarchical world of art, primacy being given to rupa, pramanani, bhavas etc. The art situation of the Mughal period with its karkhana and kitabkhana settings was not very different. The coming of the British did not change things either. The author of the book asks critical questions regarding this tradition of unfairness and wants to rehabilitate the subalterns in the history of art as far as possible. He ends his introductory chapter with this rather emotionally charged assertion – these (i.e. the labour of these people) remain unchronicled: ‘may be because these are expressed in sweats, sighs and tears – somewhat below the threshold of description.’

Let me now proceed chapter by chapter, very briefly though, skipping many interesting details and at the risk of oversimplification. In the first chapter following the Introduction, the author carefully sets the conceptual framework for the work. The framework is composed of three concepts – materiality, temporality and sociality. Materiality is not just about physical matter, but about its potential due to its association with non-physical matter in shaping the phenomenal world. Marxist and action-network theories, also other theories regarding art’s capture by capitalism are taken into account. The section on temporality deals with the changing perceptions of time, and the increasingly secular rather than religious approach associated with a kind of openness and freedom. The author transits across temporalities to allow voices from different times and places to speak in a temporally variegated present. Ultimately he writes an everyday history of art, where various layers of time are conjoined. The third concept sociality invokes Pierre Bourdieu who argued that instead of reducing or destroying artistic experience, the sociology of art can in fact enhance it. Sociology is the author’s forte, of course; but he uses different disciplinary modes to understand sociality. He also reminds us that different socialities, that is, different social, religious and economic contexts of art, can coexist within a single temporality. And also, we cannot expect sociality to be directly on the artist’s agenda. The artist only reproduces a slice – not every slice – of social reality through personal experience and imagination.

Chapter 2 – Colours, Brushes and the Sundries – locates the multiple facets of accessories. And by the way, I like this chapter the most. Colours, brushes and some other artefacts are indispensable for painting, and quality painting depends on quality art materials, which decide techniques of painting, which in turn are linked to stylistic developments. Several interesting instances are provided from early modern Europe. How in a particular painting harsh contrasts made with a bristle brush had to be softened carefully with large polecat brushes. How an important source of an artist’s favourite colours was a particular fruit in various stages of ripeness.

All this leads to the issue of labour in production and circulation of the accessories. A big part of the discussion concerns the time when Oriental colourants were becoming trendy in Europe in the age of the empire. One extreme example relates to indigo workers who underwent terrible torture to produce the coveted colour for landscape painting. Indigo was the global cross-over colour par excellence. But a more horrifying example is ‘mummy brown’, a highly-priced ingredient of colonial art. It not only involved digging up of the pharaohs’ tombs but also a process of extraction of pigments that started even while the victim was alive. The author quotes from an article by Natasha Eaton, (I feel nauseous reading it, you are likely to feel the same way, but please bear with me) – ‘They take a captive Moor, of the best complexion; and after long dieting and medicining him, cut off his head in his sleep, and gashing his body full of wounds, put therein all the best spices, and then wrap him up in hay…’ The process is described in some more detail, which ends with hanging him up in the sun and then collecting a balm-like substance from his body. There are more examples of torture and degradation. Some categories of artisans in India were outlawed as criminal castes by the British. Some of them were imported from Agra jail to serve as living exhibits of the British civilizing mission in the Colonial Exhibition in London in 1886.

Gradually, as modernity approached, actually even from the medieval period, the painter broke free from loyalty to royal/elite ideals, his authority enhanced, and he moved from marginality to centrality. The modern period saw a transition from ‘workshop to studio, apprentice to pupil, guild to gallery and artisan to artist’. Not just elites, but marginal characters like herdsmen and beggars were now portrayed in paintings. Coming to British Bengal, it is shown how commercial and socio-political interactions with the British largely decided artistic styles and tropes, along with the accessories used by the artists, which has been called mimesis by some art historians – mimesis that had slippages though. Then, Japanese wash by Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose points to a different type of mimesis in the art practices of modern India. The author notes how the importance of the ancient prescriptive texts like the Vishnudharmottora waned in the modern period, as modern Bengali painters like Abanindranath and Nandalal stressed on improvisation without caring much for prescripts and stipulations. The Swadeshi spirit created an urge to get authentic Swadeshi colours (gerimati, ela mati, bhusho kali, khayer etc.) instead of biliti paints, which called for local-level supply. However, material providers remained neglected.

Chapter 3 continues with the author’s search for the subalterns in the world of art and overlaps with the previous chapter. It attempts a social profiling of the materials and service providers. In India, these subalterns mostly belonged to the lowest rungs of the jati structure, such as malakars/malis or flowermen, whose work was crucial till the entry of colours in cakes and tubes in the modern period. For a long time in ancient India, even the artists were regarded as lowly artisans only. In the post-Gupta period, those involved in building activities, known as sutradhars, who fulfilled the needs of the ruling elites, enjoyed some advantage and figured at the top of the hierarchy of artists/ artisans organized in guilds. But on the whole, the dominance of the discriminatory caste system continued into the karkhana system of the Mughal period.

There is naturally a long discussion on the practice of leaving the artist’s identity undocumented before the advent of modernity. Perhaps in the pre-modern period – from the palaeolithic cave paintings to big projects like Ajanta to the karkhana system of the Mughals – authenticity was not of overriding importance, owing to the close cooperative relationship between the master, his apprentices and other assistants. And perhaps the artists were uncomplaining too. They knew they were serving the gods or the royalty. Also, most of these projects were beyond cash nexus. During the Mughal period, though the painter’s signature was not on the canvas, sometimes colophons in books indirectly documented his identity. But how painters were on the receiving end even then is revealed by the telling example of Keshav Das. This Mughal master painter did a heart-breaking self-portrait – the old artist showed himself as ragged, hollow-chested, bowed and emaciated, holding a petition to the emperor in his hand; but before he could present himself to the emperor, a lathi-wielding attendant advances on him, his stick raised, driving him back. (p.141).

Once again we come back to British India. Art activities vastly expanded in the British period. But caste discrimination and perception of occupational lowliness remained. Moreover, some measures taken by the British like the Forest Acts of 1865 and 1878 infringed on the material-providers’ customary domain. Even the Swadeshi spirit did not change things much. Representations of subalterns in paintings remained rare. However, the author gives us a couple of examples of how sometimes well-established artists would discover talented artists from the ranks of the subalterns. One example is the crazy artist discovered by Nandalal Bose, who made black ink from the soot collected at the bottom of an earthen rice pot and made brushes from folded cloth pieces, inspiring Nandalal to use such brushes for his famous Natir Puja mural. Somewhat later, artists like Somnath Hore and Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, inspired by communist ideology, portrayed the suffering downtrodden, but even they did not much care about the material providers. But of course, it can be asked why should one expect an artist’s sensitivity to reality to register so directly in his artwork. I would also like to add here that probably the art activities of communist artists like Somnath or Chittaprosad were not that exploitative. Materials they used were very cheap and often prepared by themselves or their comrades. One remembers how Zainul Abedin’s famous famine sketches promoted by the communists were made in black ink with a dry brush on cheap wrapping paper. For print-making which was imperative for the communists to communicate with more and more people, they used woodcut and linocut rather than the more complex method of intaglio. The communist artist Debabrata Mukherjee told me how for litho-printing he would just place a piece of wet paper on stone, press the paper with a wooden block and then keep jumping on the block for some time. (1) However, I appreciate when the author talks about the ‘humiliations of artists in the hands of the cultural and political elite of the communist party.’ Those who have read the despairing letters of Chittaprosad published later would readily agree. (2)

On the whole, this chapter is more about the frustration of the author than his success in accomplishing his mission. What he establishes is at best hypothetical. But the theme of subalternity does emerge very well from this chapter. The author ends this chapter with the statement – ‘Subalternity is variable according to situations and contexts. But it is universally forever present in everyday lifeworlds, including those of paintings’. Very true indeed!

In the colonial period an interlinked local-global chain of market for art materials developed. Chapter 4 shows how ads and the market synced. The author probes both the supply and demand sides of the market as art activities expanded and new techniques developed. Two foreign companies Reeves Brothers and Winsor and Newton are mentioned again and again. They helped Indian artists’ integration into the imperial market and the integration was mediated through shops selling art materials like G. C. Laha and Abinash Chandra Dutta Paints in Calcutta, both the firms were managed by Gandhabanik caste families, who had traditionally traded in perfumes, cosmetics and spices. Even shops in Chandni Chawk and local mudir dokans were part of this market. Indeed, there were overlaps between art material providers, grocers and apothecaries in Europe as well as India. However, internal trade gradually became entangled with the imperial market. An open art market for selling paintings was also developed. Auctions selling paintings and connecting Calcutta and London have also been discussed.

In conclusion, the author briefly reviews some writings on the history of painting in India. He also discusses the politics of morality in the world of art as modernity somewhat liberated the artist. Here the discussion is centred on the nude female body in painting as a symbol of artistic freedom.

The book is a new kind of cultural history. Let me now try to position it in its historiographical tradition. Marxists recognize art as a labour activity. This, together with Marxist concern for the exploitation of the proletariat, and the Marxist theory of the alienation of labour from his products could lead to this kind of history. However, Marxist preoccupation with the economic base as against the superstructure prevented them from exploring the latter where they thought art was embedded. Even when they did pay attention to art, they usually considered the artist’s social motive and assessed art’s role in society – revolutionary or reactionary. William Morris, an early Marxist, himself an architect and mural artist, was concerned about alienation in the world of art; but to him, it was the transition from handicrafts to the modern system of manufacture that had led to this. In his search for a transcendence of capitalism, he chose the medieval past as his utopia. (3) Needless to say, this was a misconception. Later, Walter Benjamin’s call to explore the soul of commodity did not have many takers among Marxists who would rather talk about commodity fetishism in a capitalist system. (4) Thus, despite their emphasis on praxis and material production, even Marxist cultural histories turned away from the specific densities of objects in the world of art.

As the discipline of history took a ‘cultural turn’ in the 1980s, giving utmost importance to the analysis of cultural representations, Lynn Hunt, wrote her The New Cultural History in 1989. (5) This new cultural history was also known as discursive history, its stress was on discourse or linguistic representations. Ten years later, however, Hunt wrote that the analysis of cultural representations need not dismiss the social. Rather social explanation could account for the effects of power in the cultural world, by relating the material and practical aspects of cultural representations to the social process. (6) Also, gradually there occurred a shift in cultural history from the linguistic to the non-linguistic, or to be more specific, visual representations. In 2014, the volume New Cultural Histories of India: Materiality and Practices edited by Partha Chatterjee, Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Bodhisattwa Kar (7) positioned cultural history in this strategic realignment of the social and the cultural; and showed a leaning towards the visual, using the twin concepts of materiality and practice to enable a kind of inter-textual and inter-visual history. The art historian Christopher Pinney’s essay in this volume is a good example. Thus the cultural and discursive turn in history was followed by a materialist turn. Prof. Prasanta Ray’s book is a worthy intervention in this new materialist history. It tries to understand the subalterns and their sufferings through a materialist approach.

I have not come across many such works, not at least in the Indian context. Still, let me mention a couple of recent works with more or less similar concerns. T. M. Krishnan’s Sebastian and Sons is a history of the makers of mridangam, the primary percussion instrument of Carnatic music. (8) These people have to handle animal skins, so they are all Dalits and thus caste is deeply embedded in their history, making them invisible in the gentle discourse of Carnatic music, which is mostly about the mastery of performers, their musical sensibilities and so forth. Yet it is the mridangam-makers who primarily create the sound of Carnatic music and this requires close collaboration between the maker of the instrument and the performer. All the mridangam-makers get in return is back pain and routine harassment at the hands of the police on suspicion that they trade in illegal animal skins. They are not allowed inside the puja room of the musician’s house, even though the instrument made by them is worshipped there. Some of them attempted to perform but were shunned and shown their place.

This kind of injustice is to be found prominently in a sphere where there is no sharp line of distinction between artists and artisans and which is labour-intensive, like sculpture. Let us take a more specific example – the Durga Pujas of Kolkata. Tapati Guha-Thakurta’s book In the Name of the Goddess alerts us to the injustice in the world of Durga Puja. (9) This traditional artisanal domain in all its aspects – idol-making, pandal-making and lighting – is turning into a new world of art in the present era of Theme Puja. The old artisanal world survives as a thick layer in the new world. Yet it is only a few among the idol-makers who have become known as artists or sculptors by dint of their training in art colleges, and only they enjoy the benefit of the increasing capital flow. Others have to eke out a miserable living. Similarly, in the sphere of pandal-making, only a few decorators are known as designers today, despite the indispensable skills, continuous adaptation to new ideas and techniques and overall great contributions of the rest.

The book by Professor Prasanta Ray is an excellent example of this new materialist history of art. I hope it will inspire more such works.

References

1) Anuradha Roy, Cultural Communism in Bengal 1956-1952, Primus Books, 2014; the chapter entitled ‘The Political within Pictorial and the Pictorial in Politics’.

2) ‘Chittaprosader Chithi’, Parichay, Autumn issue 1981 (a collection of letters written by Chittaprosad to Murari Gupta of Lucknow).

3) Maynard Solomon ed., Marxism and Art: Essays Classic and Contemporary, Harvester Press Limited, Brighton, Sussex, 1979; the section on William Morris (pp.79-90), particularly the excerpt from Lectures on Socialism and Signs of Change.

4) Ibid., the section on Walter Benjamin (pp. 541-561), particularly the excerpt from The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

5) New Cultural History edited and with and Introduction by Lynn Hunt, University of California Press, 1989

6) Partha Chatterjee, Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Bodhisattva Kar eds., New Cultural Histories of India: Materiality and Practices, OUP, India, 2014 Introduction

7) Ibid.

8) T.M. Krishna, Sebastian & Sons: A Brief History of Mrdangam Makers, Context, Chennai, 2020

9) Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata, Primus Books, Delhi, 2015

Anuradha Roy, retired professor of history, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, specializes in intellectual and cultural history with special reference to Bengal. Her book Cultural Communism in Bengal 1936-1952 deals with visual arts among other art forms.

Read More>> Please Subscribe our Physical Magazine