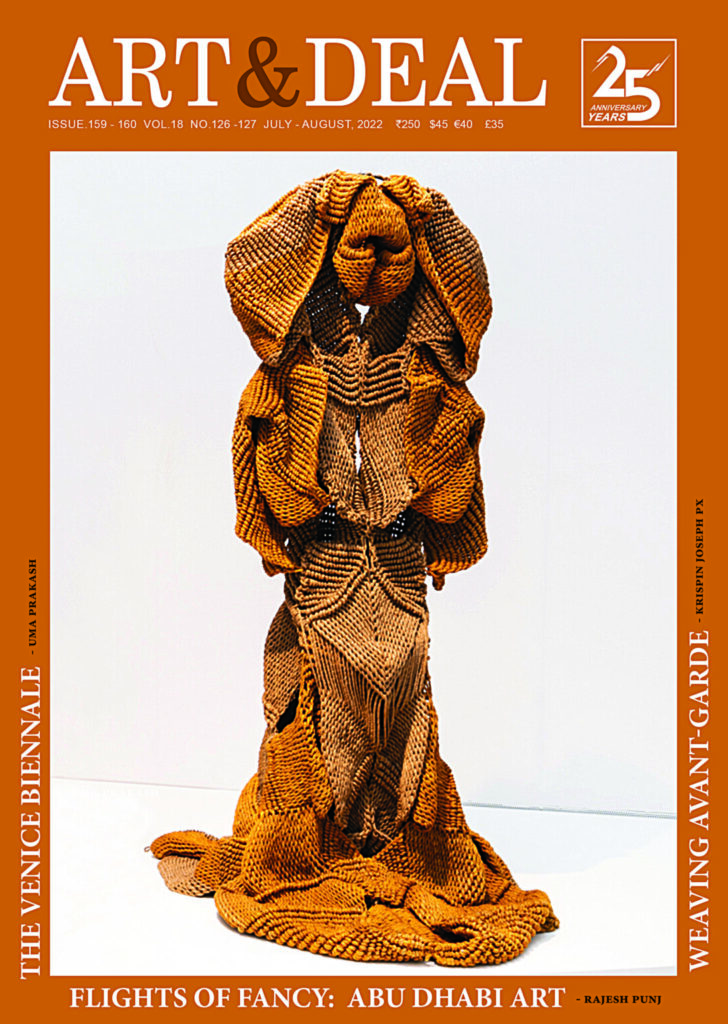

Re-Structuring Romanticism – No child’S Play IndIra Purkayastha ghosh’s neo romantic sculptures on contemporary childhood.

Rahul Bhattacharya

Contemporary India is witnessing its own tryst with modernity. Unlike in the colonial times or even in the decades post-independence, this version of modernity is powered by a technological-financial machine which is globalised, post-national and almost post-human. Of course, this neo liberal, postcolonial modernity, like the one of the past comes to us garbed in a creative grand narrative, powered by visions of a machine lead globalised era; yet, as it powers on, it leaves behind residues of loss of utopic visions and a disengagement with the earth itself. Possibly, the manifestation of this comes through in our increasing disconnect with our dayto-day.

There are spaces and moments in our lives that just go by, often unnoticed in our day to day business living and succeeding. Perhaps our continuing fascination with innocence has ensured that children continue to evoke a romanticism. This feels special at a time when our emotional disconnect with ‘nature’ is almost complete. In today’s collage of realities, desires and dystopias, the ‘child’ has remained as the only connection between hope and future. Yet, in a neoliberal India, romanticism today can no longer be reactive to modernism and in deep empathy with the pre-modern. Romanticism can now be felt as the irresolvable tension between modernity, tradition and contemporaneity. In aesthetic terms, the key is to understand romanticism is, as a sense rather than as a system of thought, a sensibility rather than a paradigm, an attitude which needs to discover its own expressive language. Indira Purkayastha Ghosh’s current body of work is rooted in this tense romanticism, the ‘child’ for her becoming a ‘rabbithole’ into the tragic and the sublime, creating the possibility of an ironical, critique of our times, playing with both desire and apathy.

In a decade dominated by conceptual art and at a time when the discipline of sculpture has been overtaken by installation, Indira’s work comes as a gush of fresh air, opening up new horizons contemporary Indian sculpture. For her, it is important to make sculptures that have the power to evoke emotions, to create some warmth in this world of coldness. Over the last many years, she has been practising and evolving a sculptural language deeply engaged with nostalgia, materials and narration. Through these engagements, she has developed a personal articulation of contemporaneity which is a powerful ‘alternate’ to the neoliberal aesthetics which largely defines it.

"Being based out of Raipur gives me an edge; it gives me a new imagination of contemporary life which is difficult to access from the centres of Delhi, Mumbai or Kolkata. Chhattisgarh being a tribal state, has its own aesthetic tradition and visual culture, as a sculptor, I feel anchored by it. Being a teacher keeps me connected with children, playfulness and fantasies. "

As a child she grew up in the hills of Chhattisgarh playing with adivasi children. This experience grew seeds inside her, which grew to always connect her with notions of purity and a beautiful sustainable relationship with the environment that comes to as an almost primordial language. Possibly, her love for the sub conscious innocence, the playful, the narrative took roots within her during her childhood and her experience in teaching art to children re instigated her memories buried deep within the pressures of a grown up urban life and art school education. This enables her to develop a critic of contemporary culture.