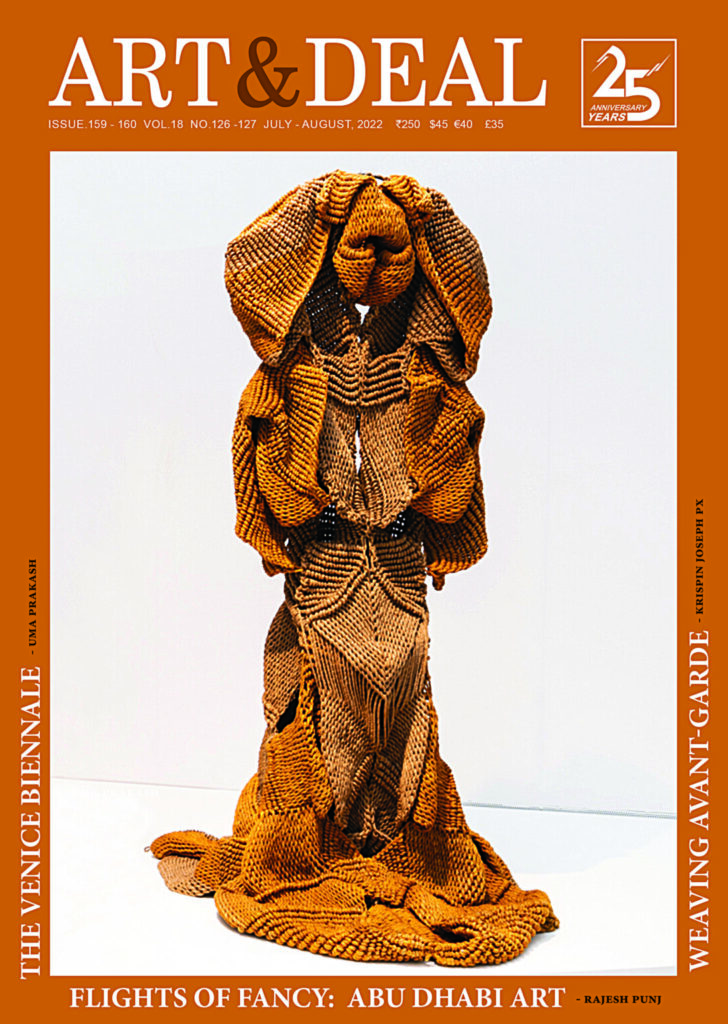

Glass Architecture

Jean-Michael Othoniel interview

Rajesh Punj

In his early correspondence on glass, seventeenth century Italian glassmaker Antonio Neri referred to the Roman author and natural philosopher Pliny the Elder, who cited that its origins could be located to the mouth of the Belus river in Northern Syria, ‘by merchants driven thither by the fortune of the sea, – making fire upon the ground, where there was a great store of this herb which many called Kali. This herb burned with fire, and therewith the ashes and salt being united with sand or stone fit to be vitrified is made glass’, all the natural elements combined to create liquid gold. And for Saint-Étienne born, Paris based artist Jean-Michel Othoniel, Neri’s sand and stone substance has become a leading elixir for his own modern imagination. As the artist has over time applied himself to creating transformative works that under his influence manifest as a series of bold and very beautiful artworks.

Giving glass gravitas, Othoniel appears as animated as he is positively enslaved by the anatomy of this age-old coloured compound, as it has become the transparent flesh and bones of many of his more memorable works. Explaining how “Glass has opened up, as we have discussed, a realm of endless possibilities, and today I am willing to go even further in the creation of pieces that see them as more than sculpture, in order they can become real ‘glass architecture’.” And as German author Paul (Karl Wilhelm) Scheerbart sought before him, Othoniel intends to illuminate the world with his translucent masterful works that in and of themselves encapsulate the elemental order of the universe.

Enlightened by the 19th and early 20th century visionary, Othoniel says of its visual appeal, “I can’t help but imagine creating works on such a scale, people could enter them, climb them, and live with them: whereby sculpture, architecture, site specific works, art and day to day life are porous notions that I am trying to split and merge.” By which the premise and politics of such ideals had Scheerbart exalt the virtue of ‘glass houses built deep into the sea’, as a utopian alternative to the brutalism of brick buildings. Opening his own glass window onto the world, Othoniel finds purpose in creating works that for their material form are as intimate, as they are overwhelming. Citing a definite duality between micro and macro sensibilities, as though materials are as much human as they are human made, Jean-Michel Othoniel sees scale as integral to an audience’s experience. Declaring, “The desire to scale up my work was a challenge, glass as everyone knows is very fragile, and at the same time I found there was another duality to explore and create works on a monumental scale, both delicate and strong.”

In 2015 as one of his standout works, Jean-Michel Othoniel created The Invisibility Faces series that were housed in a concrete cathedral outside Basel. Designed by German architect Rudolph Stein in 1924, this Gesamtkunstwerk (for the synthesis of diverse artistic media and sensory effects) as avant-garde architecture proved the ideal setting for a series of cut-glass self-portraits. For which Johannes Nilo, director of the Goetheanum, saw Othoniel’s series of blank busts as ‘earnest and timeless kings sitting on their wooden thrones’.

But more than that each of his obsidian sculptures appear as these melted monuments to leading men and women who might well have interrupted or influenced the course of modern history.

“I showed The Invisibility Faces for the first time at the Goetheanum near Basel in 2015, and the sculptures resonated astonishingly within this unique environment. The concrete building acting as a jewelled case in dialogue with the works, since the large totems of obsidian and wood with their angular and organic shapes could be likened to the building that housed them. Concrete, wood, glass, the materials mingled in harmony in an almost carnal way, allowing for an awakening of the senses.” Which led to parallel projects such as Versailles, (as a fountain for a King), Angoulême, and a work resembling Katsushika Hokusai’s 19th century print of a great wave. Entitled The Big Wave Othoniel’s surge of static ocean water is made up of hundreds of coloured glass bricks. Major works that required of the artist his fundamental need to “work in parallel on a series of intimate almost secret works, bearing a meaning that only I could understand at the time; an escape you could say, like Dorian Gray’s painting.” As glass has for Jean-Michel Othoniel become a model material that has allowed the artist to create a more translucent vision for the world. Jean-Michel Othoniel’s next exhibition Face à l’obscurité is at Musée D’Art Moderne Et Contemporain, Saint-Étienne Metropole, from the 26 May – 16 September 2018.

Interview

Rajesh Punj:

To borrow my first question from your book, ‘why glass?’

Jean-Michel Othoniel:

I was using sulphur in my early works, and in 1989 I decided to actually go and see sulphur in a volcanic setting, on the Eolien Islands close to Sicily, and whilst there I met a French volcanologist and archaeologist, who introduced me to an element called ‘obsidian’, the chemical compound for volcanic glass. And like an alchemist, I began exploring how to manufacture obsidian artificially at the International Glass Research Centre(CIRVA) in Marseille. Having a passion for metamorphoses, sublimations, and transmutations of all kinds, I decided to focus on glass, and went onto work with glass blowers in Murano, Venice; and I showed my first glass works during my residence at the Villa Medici, Rome in 1996. Ever since I have chosen to explore with the greatest of pleasure a material that effectively crystallises all of my desires.

———————————————————

The Carré Sainte-Anne, Montpellier, showed some fifty of my works, which are part of my personal collection; and it proved more of a retrospective look on my own work. Like an enclosed garden or a dream world, the work Map of Tendre modestly showcased the works as a precious talisman. I have kept all these key pieces in a collection of my own works in order to be able to go back to them, and as a way of rejuvenating my energy. And I decided to show in this former church, the pieces that I have been collecting since the 1990s, when I initially began to take on an interest in glass.

———————————————————

RP: I was lucky enough to attend your combine exhibitions, Géométries Amoureuses at CRAC (Centre Régional D’Art Contemporain Occitanie) Sète, and at La Carré Sainte Anne, Montpellier, where a whole body of works demonstrate your devotion to glass. Can you explain those two exhibitions, and of your having situated works at the former church in Montpellier?

JMO: This double event, under the single title Géométries Amoureuses presented many facets of my work through some sixty sculptures, a dozen paintings, and more than a hundred works on paper. By itself, the title unites the dualities that characterizes the main theme I am working on since the very beginning: of sensuality and rigour, the hidden and the revealed, and of pain and its relationship to beauty. The CRAC exhibition in Sète presented an exhibition composed of a new series of monumental works. Inspired by the forms of nature, it presented a journey close to a radical, monochrome and abstracted architecture. These new works of glass, mirror, metal, ink and obsidian, showed how my practice has further evolved since my retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2011. It showed an audience the new issues and ideas I am currently exploring.

The Carré Sainte-Anne, Montpellier, showed some fifty of my works, which are part of my personal collection; and it proved more of a retrospective look on my own work. Like an enclosed garden or a dream world, the work Map of Tendre modestly showcased the works as a precious talisman. I have kept all these key pieces in a collection of my own works in order to be able to go back to them, and as a way of rejuvenating my energy. And I decided to show in this former church, the pieces that I have been collecting since the 1990s, when I initially began to take on an interest in glass. Trying since then to retell the key moments in my own journey through this glass period.