If the machine is a measure of the modern experience, then Damián Ortega’s October exhibition at Centro Botín is an inspired ‘object-hoard’ of the anatomy of our lives; leading to his perfected examination of the universe itself. The Mexican artist’s exhibition, one of a number in recent years, inhabits and adds substance to the Botín building’s elastic interiors. Elevated from the water’s edge, French architect Renzo Piano’s semi-circular structure challenges everything of the Spanish city’s landscape, to offer its citizens this alien-like aircraft to art, and as much as Piano’s innovative design is held aloft by pillars and posts that hark back to something of his predecessor, Le Corbusier; inside the artist appears motivated by a more earthly energy, of profiting more from prizing everything apart.

As with Cosmic Thing (2002), a critical work for the artist, after burying his Volkswagen Beetle, it appears resurrected, his having suspended everything of the car from the ceiling as an unimaginable puzzle that, as the audience, we mentally want to will back again—a car is a car, its parts invisible, and its disassembly destabilising. The Beetle type 1 is undone of its body parts, bereft of its steering wheel, its engine and wheels – its transformation from object to art complete. If Beetle ‘83, Escarabajo (2005) is symbolic of the death of the automobile, then Cosmic Thing takes us back to its birth, and the engineering of its iconic appearance. The material parts of an industrial dream that when given the instantly recognisable shell, have become as much a part of our modern life as the technology of the television and the refrigerator. Carried by such inquisitive interests, Ortega insists, with some sentimentality, that the machines that serve our interests are mesmerising, for our devotion to them. That they live, exist, and then die by our hand, in the way the human is subject to its own fate. The anatomy of our aspirations, and objects – material and mineral, are central to the installations that follow.

Adjacent is a work entitled Harvest (2013) that initially appears as a school of eels pulled from the waters beyond this futuristic building, but on closer inspection, these black threads have the look of iron rods, used to delineate makeshift spaces. Disregarded, Ortega manipulates them into what might appear as random shapes, but as with everything, they are far from impulsive, their individual shadows revealing a letter that offers the audience the entire alphabet, in the manner, his mother would have written the letters out on paper; which reads as a remarkable testament to their lasting relationship as well as the artist’s spirited imagination.

For Ortega, it is as if the individual spaces that were offered to him for this exhibition became laboratories, taking the space as zero and looking at everything new. As places of research, the exhibition rooms emphasise the energy of the artist’s curiosity, for his fragmenting everything as art. Threading each piece, until he has, for all his creative ingenuity, what appear as atmospheres of art, that hang preciously but still manage to hold their own, as if overnight the world has ruptured off its sensibilities. Irrational occurrences that he would want us to believe are not designed to damage our lives of their detail in any way, but offer a view of the world, as we might never have seen it before. To look at Ortega’s works, his sculptures and carefully choreographed installations, is to feel something of his imagination, as he appears to want to excavate our earthly possessions and start again. Putting a greater emphasis on the individual elements, and not giving us the complete object as an answer, Ortega sees the substance of our lives as being decided not only by that which holds everything together but as much by the forces that tear everything apart. Equal and opposite, the science of his sculptures is intended to explain his art as influenced as much by origination as annihilation. The beginning leads to and allows for the end and the reincarnation of the rules that are paramount to our understanding of Damian Ortega’s work.

Ortega himself talks about the ‘atmosphere of everyday life’ when referring to the recent work Domestic Cosmogony, to which he introduces the simplest things in front of him, to create a survey of the ordinary, against a background, born and based in Mexico City, of bureaucracy and political poverty. And in that work, it is as if Ortega celebrates the extraordinariness of the ordinary. That we all have these elements to hand, that they exist within our universes, and are recognisable and resonate for everyone—for Ortega explains more of what it is to be alive, and living, than the abstracted ideals of loftier interests. The ordinary and the utilitarian again appear central to the older work Controller of the Universe (2007), which has something of British artist Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Material (1991), about it. The ‘Controller’, its title, refers to Mexican Diego Rivera’s mural Man at the Crossroads (1934), which depicts man controlling the modern machine, and with it the density of mankind. Ortega’s installation consists of an impressive array of tradesman’s tools intended to cultivate and create everything in our lives, each of which he characteristically suspends from the ceiling. Removing them from the earth, already tarnished by their working history, Ortega elevates them into space, as they hover closer to the heavens. And for their fantastic configuration, the artist transforms them into the machinery of the universe, as if everything that becomes invisible can explain something of the universe to us. The unremarkable is what Ortega returns to again with the work H. L. D. (2009), which has the artist take a wooden chair and magically prize it apart, to celebrate its utilitarian intention. It hangs, as with everything of the exhibition, poised between coming apart entirely or, for the will of gravity, reappearing whole. And then there are the other works, entirely elemental, dust-like, that reveal Ortega’s interest in the anatomy of matter. As experiments, the artist takes, for works like Journey to the Centre of the Earth: Penetrable (2014), and Stardust (2016), the slightest of materials, often colour-coded, to create these impressive particled pieces that are equally made up of unusual and everyday elements, carefully choreographed into space, as evidence of his as well as the outside world’s creative energies.

Interview

Centro Botín: We also invited Damian Ortega to contribute to a solo show, and at the same time, we want him to direct our workshop that will be here in Santander next month; which acts as the two parts of his invitation to be here. Regarding his exhibition Expanded View, we have an artwork outside, a video. This is special because the exhibition presents nine works that appear as big installations, and this is a smaller, more intimate, projection, and the artist wished to have it separated from the other works, but it is still very much related to the works in the exhibition. The work Beetle ‘83, Escarabajo (2005), shows the artist driving his car, a Beetle, to the Volkswagen factory in Mexico, to bury it. So, practically, you can see he and his assistants make a very big hole, in the earth and lay the car in it, before covering it over.

Rajesh Punj: This has me thinking of the American artist and inventor, Richard Jackson, who has also employed the car in art, in incredible ways. I saw him in Zurich some months ago, and he recited a story about his being involved in a near-fatal car crash, in which the other driver died on impact when he survived; and of how he wished to recreate that same energy, activity/event, by filling two coloured cars with paint, and whose choreographed impact leads to a creative incident; and so is this film from the 1970’s, or much later than that? It appears to be quite old, but it could well be intentional.

CB: It is in fact from 2005, which he filmed with a 16mm camera, and where he employs a team to lead the car to its death and burial.

RP: So he was here some weeks ago now.

CB: Yes, for the installation. Damien is based in Mexico, and in Berlin in the summers.

RP: I am trying to remember Damian’s gallery.

CB: Kurimanzutto in Mexico and White Cube in London.

RP: I wonder what Volkswagen themselves make of the work?

CB: We have had no response. For the film Beetle ‘83, Escarabajo (2005), Ortega drove from his house to the Volkswagen factory, and there he buried the car, very much like the insects that come home to die.

RP: And also upside down, I wonder if the insect dies like that?

CB: Exactly.

RP: The car takes on the characteristics of the creature.

CB: He wanted to have a funeral for the car with his assistants.

RP: Which proves interesting, when you consider how they (Mexico, South America) understand death.

CB: Yes, of course. A celebration.

RP: With the ceremony complete, did he remove the car?

CB: Yes, because he feared parts or pieces of the car being taken, and the work is about everything we recognise of the car, as with the work inside the exhibition. It involved his own car, and the one that you see is not the same as the one inside. Damian wanted to have the car hanging against the city, so you have the Beetle with Santander behind it.

RP: The suspended car is from 2002?

CB: Yes, Cosmic Thing was created when the car was out of production in Mexico.

RP: And with the car’s renovation and redesign, it became something entirely else.

CB: Yes. For the artist, this particular model was special because it proved ideal for an artwork of this kind. The parts are designed in such a way that they can be easily removed from the chassis.

RP: And is it that Ortega was originally a mechanic, or is it more an intuitive interest for everything? I can imagine, for any faults, him fixing his car regularly, to become more familiar with its body and basic parts.

CB: For this work, Damian needed a team to install the work, and as an installation, it illustrates how curious he is about how something comes together, and how the car’s components are set inside one another.

RP: Which we are never aware of.

CB: Exactly. For Ortega, this installation is a way for us to appreciate all of those visible and invisible details.

RP: You refer to assistants for the installation of this work, how many were involved exactly?

CB: He had twenty people here for two weeks, and with Damian, for his attention to detail, he was here the entire time working with us, ensuring everything was correct.

RP: I can imagine the air of precision that is required for such a work.

CB: It is special because he decides the distance between the elements onsite and in situ.

RP: So every time he showed this work, it was seen differently.

CB: And Damian responds to each space very differently.

RP: This makes it interesting when thinking about the work in space.

CB: What we did, because we were working on this show for two years, was to decide where the walls would go, and then together with the artist we decided on the dimensions of the car, in terms of the greatest distance, side to side, from the back to the front, we wanted the audience to still be able to walk around the work.

RP: So these are all false walls, which you have measured in to decide on the final space.

CB: You need to remember the architect/designers conceived of this space as empty, with the outer edge walls, the glass to the ceiling, and the glass to the sea. And within the spaces, we have a framework that allows artists to hang works, which is what convinced Damian to have the show here. This is something that happened with German artist Thomas Demand, for whom the gallery was made empty, and within that, we hung eight wooden pavilions, to which he added his cardboard photographs.

RP: It sounds as incredible as this, and something I wish I had seen.

CB: That is what happens here—that the gallery is made different for every single exhibition, with the natural light, the walls, and the ceiling.

RP: And artist for the artist, you paint the walls and design the exhibition, as explained.

CB: All of the artists we work with, are always incredibly excited by the opportunity to come here because they can determine, like no other place, a site-specific project, that becomes unique to us.

RP: So it is different in the sense that the space is quite elastic, becoming unique to everyone’s needs. So for the artist, it is a major exhibition, but for you as an institution, it is a major undertaking as well.

CB: We always have to consider how to do something, for example, the artist’s desires have to be understood and executed according to what the building can offer.

RP: Going back to the Beetle, is this the same car that has been seen and installed in different locations internationally?

CB: Yes. This became famous for it having been shown at the Venice Biennale in 2003, and then it was shown again in different places, I believe Damian has two exhibition copies or two versions of the car.

RP: I wonder how many of these types of Volkswagen Damian has in total?

CB: Two or three as far as we are aware, from the one he originally showed at Venice. And with the hang, if you look closely, you can see the different thicknesses in the steel threads, depending on the weight of the object. For example, the engine has a greater strength of thread than the smaller cogs.

RP: And so this is the universal version of the car, that appears to have been taken directly from the production line, without a chosen colour that might engender it to a specific location.

CB: Damian told us that he saw an advertisement claiming that five people could extract and separate all of the parts of this particular car in three minutes; which is why he wanted to try and do so himself.

RP: As I mentioned, the work recalled the work of English artist Cornelia Parker, specifically ‘Cold Dark Material,‘ which is the fragmentation of a garden shed, every element hanging as Damian’s car.

CB: In a way, this is a ‘big bang’, with the pieces ordered and organised.

RP: Determining the precise location for each of the elements whilst considering the whole, is beyond my imagination, and for that, there is something entirely German about it.

CB: The car is German. Damian had a studio in Berlin, so he lived there for some years. Now he is back in Mexico, but he still returns frequently to Berlin.

RP: It appears to be the perfect emblem for his relationship between two counties, a car that has successfully crossed two continents. But I think in Mexico City these are the cars still used as cabs – green and white.

CB: The car was really popular in Mexico.

RP: You can see it epitomised the working classes, for its simplicity and honesty, and then the Beetle, when we think of it, is entirely about its functionality, and not the aspirations of car makers now.

CB: It was affordable and easy to maintain, for everything we see of this installation.

Plaster balls covered in bee wax, cotton thread, stainless steel

wire and 5oz. lead weights

Installation. 290 x 550 x 1800 cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Ciudad de México and

New York

RP: A car for beginners in a sense, and with that in mind, it becomes interesting to think about how he and his country saw the car, as something much more than a machine. You can imagine that at a certain moment, it became integral to their lives, in a way, for the surplus in Europe, we need not understand anymore. Of a car offering everyone a means for them to live and to exist, not as kings but as countrymen.

CB: And then there is his wish to consider the car as a mammal, and the car without its elements as a skeleton. If you think about when you enter a natural history museum, you would envisage seeing an extinct creative, dismembered and perfectly displayed, and he was thinking like that.

RP: Yes, of course, the car as a creature, and you already mentioned Damian being here for quite some time.

CB: He was, for every day of the installation he was here, working with us, contributing to the process when he was creating and installing.

RP: I can imagine it being quite something working with him, and I wish I had been present.

CB: He was very easy to work with, unlike so many artists.

RP: Yes, of course, too many artists can be more motivated by their ego. I can imagine Thomas being quite ‘demanding’, if you excuse the expression.

CB: He was very precise as an artist but in a different way.

Jahel Sanzsalazar: Coming into the work Harvest, you might imagine the snake of sin, which is what the Catholics tend to think of, which likely you won’t because you are not Catholic.

CB: Damian started life as a cartoonist for a popular newspaper in Mexico.

RP: Okay, he was drawing, to begin with.

CB: So he was very familiar with the line. But I wanted to add, that this work references popular street graffiti, and he has created a series of sculptures in this way, of lines that appear meaningless. But, there is something quite incredible, which possibly you haven’t yet noticed, that these lines are a series of letters that appear as shadows on the floor, making up the alphabet, and each of these recalls and resembles exactly the handwriting of the artist’s mother. So there are two parts to this installation, the one that you see as a sculpture, and then what you are given on the floor.

RP: How interesting, because when we initially came into the room I wondered why I could see forms as letters, but now I realise why because each one is a letter.

CB: Exactly, and the light is part of the piece, projecting the shadow onto the floor.

RP: And again, this a work that has to fit into the space, in a way that makes it feel permanent.

CB: Harvest was intended for this space, because of the lighting and it being, for the false walls around it, more enclosed.

RP: And I assume that the patterning of the wooden floor was something Damian was happy to accommodate.

CB: There are so many elements that are integral to the building that all of our artists have to allow for, and work with.

RP: Again I would think these individual rods are heavy – with everything fabricated in Mexico and shipped here for the show.

CB: Damian refers to different specialists for each of his works, depending on what is required. Another work that has been shown in many different places, and is part of a private collection.

RP: The work’s title has me thinking as well, Harvest, which suggests so many things.

CB: With the opening, it was the first time his mother saw the work. She studied calligraphy in a French school and was having to practice and repeat it on paper until it was perfect; again, again and again. And I think it is beautiful to have mixed graffiti with calligraphy.

RP: Of a looser, more open form of expression coupled with something so precise, and having one allows for another.

CB: And of the letter appearing perfectly on the floor, as it should, from what we know of his mother’s understanding of calligraphy.

RP: It might also explain how language has evolved, and how language, as we use it, is as important in an urban or academic setting.

CB: Graffiti is something you cannot control.

RP: Of course.

CB: Beyond Harvest, this part of the show is divided into five sections, for four different artworks and four very different installations. This work is Controller of the Universe (2007), which is a sizeable installation of working tools that Damian collected while living in Berlin. There are tools for carpentry, gardening, construction, and architecture; and the installation is divided in such a way that the audience can walk into the work, and feel everything of it from within. And again, every one of these elements is perfectly hung, with Damian creating a wooden frame to support the individual threads for each object, in order he was able to find the correct positioning and perspective. There are also new items added because the artist wanted to include others.

RP: Making the work specific to the location. So every time the work is shown it alters and at the same time evolves.

CB: Yes, for example, this work includes one of our hammers.

RP: Again, it feels very German, for his including so many German tradesman’s tools, and that offers something interesting, if you were to consider the work coming from Mexico or the Middle East, how so many of the elements would be different; revealing the geography of the work.

CB: Also the title of the work is related to a mural by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, and if you remember, Rivera’s work was originally conceived for the Rockefeller Centre in New York, and recreated, under the title, Man, Controller of the Universe, in Mexico. The other works are more related to volcanic rock formations, minerals, and the geological part of his work. For example, in the installation of Stardust (2016), you can find different objects, including the more rudimentary—a pen, glass, bricks, bread, and tubes—and the artist introduces different gradations of colour—as well as corn and paper.

JS: I am trying to understand the mind of this man, who likely refuses to throw anything away.

CB: Whilst always collecting something new, Damian was in love with the drawings we have upstairs because this work is related to the cosmos and space.

RP: It really must be quite something to install, an operation in itself.

CB: Damian’s Volcano (2016); has two volcanoes meeting in space. One is made entirely of volcanic rocks; the other of glass from bottles and glasses, and this is a work that can be installed in many different ways, again depending on its location. Here the work is spread over five metres, but this work was installed twice as high, somewhere else, so it has appeared very differently.

RP: And I assume it cannot be that each piece goes in a particular place, as they appear unlabelled, or are they labelled? I wonder how he determines where each of the pieces goes to be able to create this perfect volcanic ‘V’ shape.

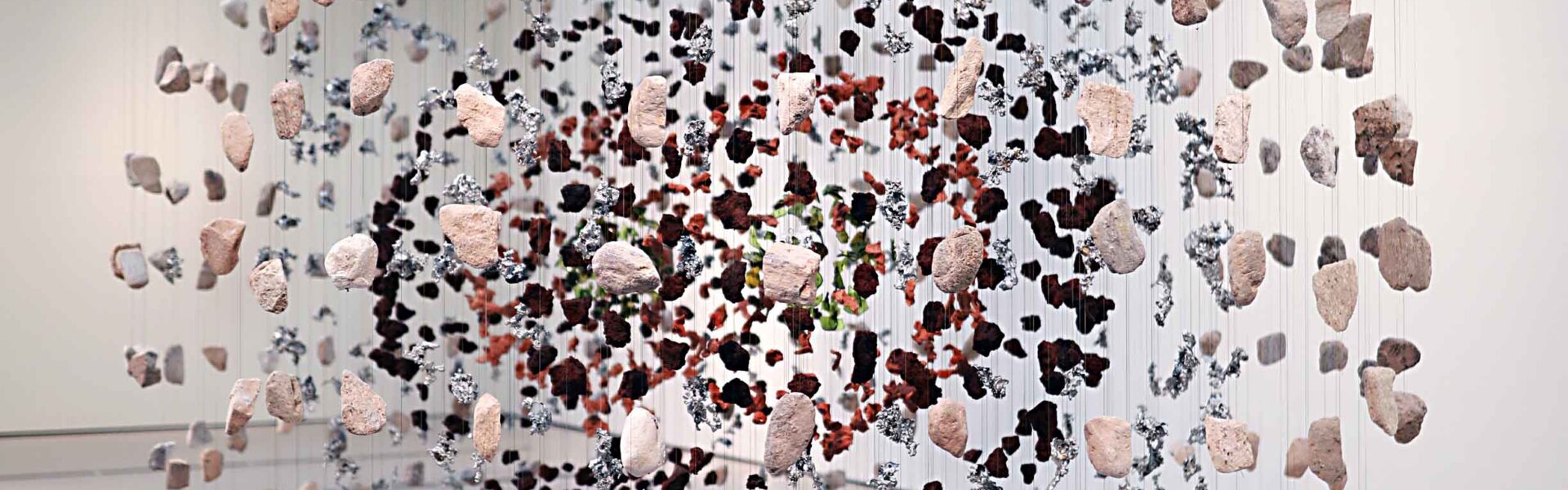

CB: All of the pieces have a reference number that he refers to when installing and reinstalling the work, and with that, the work can only be installed in one particular way. There is as well a system that is marked on the framework above the sculpture that requires you to put the right element in the correct place, and with that, the volcano appears. And then there is Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Penetrable (2014) another work that is related to the cosmos, and you can notice the different shapes, not only of the choice of colours but the materials – of the rocks, the metals, the ceramics and glass. And for the perfection of the hang, the work appears as a perfect sphere. With these four works, as they appear in this space, Damian insisted that they look like renderings, when you are working on the digital process of shaping or constructing something, it looks to him like that.

RP: I find the works with ‘readymade’ objects stronger in many ways, because of the visual transformation that takes place, with the dust and debris pieces there are more ephemeral and less altered. But possibly I am being too obvious, seeking something immediately. The initial works have a real presence where as these works appear more atmospheric.

CB: Then we arrive at Warp Cloud (2018) which takes its inspiration from Japan. A work that was made for a site-specific factory there, specifically an abandoned building where he was invited to create something for the space, and he talks of how he felt the humidity that led to his creating this big installation, which looks like individual drops of water, frozen in the moment, as well as the molecular structure of water particles. Installed it appears like a cloud, and the audience can see the work in the round because the individual channels allow for that. Each ball is made of plaster and covered in beeswax, which is why they are slightly shiny, each of which is attached to a series of weights that hold everything in place.

JS: Otherwise they are likely to move

CB: Exactly, which creates the work’s equilibrium.

JS: And there are two sizes of balls?

CB: Yes.

RP: Again, I go back to the idea that I couldn’t imagine this kind of precision for a Mexican. Berlin, Germany, clearly had quite an influence on what Damian was doing and how he went about executing it.

CB: It is precise, but in a manual way, for including ordinary objects, and applying simple processes.

Plastic, aluminium, bronze, steel, glass, tezontle, pumice, brick,

clay, wire, concrete, wood, scourer, sponge, organic material,

nylon thread, painted plywood

Installation. 175 x 350 x 110 cm, Private Collection

RP: Again, there is something very mathematical about the work, likened to atoms, positive and negative. And I assume this piece, like the others, can be altered to fit the space.

CB: Leading to ALAIS, a project Damian began in 2006, with a copy of Marcel Duchamp’s writing. At the time, Damian didn’t speak English incredibly well and had asked his colleagues to translate the volume into Spanish, and with that, he decided to publish it very cheaply, to share it with other artists who only spoke and read in Spanish. That is how the editorial part of his practice started, and now he has many publications that have been translated into Spanish to be able to share the books with his contemporaries in Spain and South America. And finally, we have the work Hollow/Stuffed: Market Law (2012), a submarine that is full of salt. Activated by prodding at the belly of the bags, there will be a moment when the 1,400 kilograms of white powder will be released onto the gallery floor.

RP: So the artist has asked you to intervene upon the work, to trigger the stream of salt?

CB: It can be that it falls of its own accord, but sometimes it requires we act upon it, and encourage the salt to fall.

RP: And I assume it is at such an angle that it won’t fall within an hour or so, but that it falls methodically, and over time.

CB: Exactly.

RP: And it is that everything will empty onto the floor? It has been shown before and achieved that?

CB: It was clear from the beginning that this would be the best space for this particular work.

RP: It is against the water for the view. And I wonder why a submarine?

CB: Damian showed from newspaper cuttings that drug traffickers had a submarine to transport illegal narcotics from one part of the country to another, and in a way he does the same, mimicking them, filling the fabric submarine salt.

JB: And the vessel is made from salt, flour, possibly even explosive bags, for the symbols on the side of the bags that have been stitched together.

RP: And it sits so well against this view of the sea, as I said. And as much as it is so impressive, I can imagine it must be quite a difficult room to curate a work into.

CB: Yes, it can be difficult. Vicente Todolì, who is the president of Centro Botín’s art committee, curated this exhibition, determining the programme and exhibitions.

Read More>> Please Subscribe our Physical Magazine