AlFann

The English writer and explorer Wilfred Thesiger in his much admired book Arabian Sands 1959, saw of the untended desert the simplest way of life, where “a cloud gathers, the rain falls, men live, the cloud disperses without rain, and men and animals die.” A landscape intended for the foolhardy as well as the favoured, as he would later confide in his memoirs, as a “cruel land” that could “cast a spell which no temperate clime can match.“ And more than half a century on, Thesiger’s untamed terrain has since become the playground for a country less isolated and more involving of everything the Middle East has to offer. With his footprints having long since disappeared from the shifting sands, their historical indentation driven over my convoys of off-road vehicles, that takes a new kind of trailblazer from the serenity of their desert tent to the areas earmarked for land art; the artist having since become the modern polymath, for their taking on the role of pioneer.

Transformed under the rule of the young Crown Prince, who has seen fit to alleviate Saudi Arabia of its reliance on oil based industries, for a ‘vision 2030’ plan that has its people at the centre of a cultural and consumer revolution. And as quickly as the major brands have cashed in on the more open-minded ideals, so art has taken on a ‘story-teller’ significance, in a region where the myth has a long-standing majesty. Leading the way is Iwona Blazwick, recently appointed lead curator of contemporary art for the Royal Commission Arts AlUla project. Formerly Director of the Whitechapel Gallery, London, Blazwick appears unperturbed by the criticism that comes with her appointment, for what has been explained as an ‘art wash’ of the country’s human rights record, and that she sees as an opportunity for a ‘greater freedom of expression’. In no way politically motivated, Blazwick’s ideals are more philanthropic, as she softly explains the ability of art to offer new ideas, to a country looking to introduce itself to the world. Speaking weeks after meeting in Riyadh and again in AlUla, the site of the Wadi AlFann, or ‘Valley of the Arts’, that resembles the set for a science-fiction film, Blazwick eloquently explains the region’s isolated, arid yet stunningly beautiful desert, that once served as the Silk Road and Incense Route, and is now, she considers, ideal as a crater for contemporary art.

Exceptional in how she understands everything of the task assigned to her, Blazwick leads a team of talented individuals, made up of Saudis and those that have been sought after from further afield, to decide on a choice of landmark sculptures, that deliver the same kind of biblical brilliance offered by American Richard Serra’s East-West/West-East 2014, that rises from the earth to the lowest edges of the sky, in the Qatari desert. As much a moving and ‘mysterious’ landscape for Serra, as the Saudi desert was for Wilfred Thesiger in his day, Blazwick sees that enigma as offering her artists an arena that insists on being conquered again.

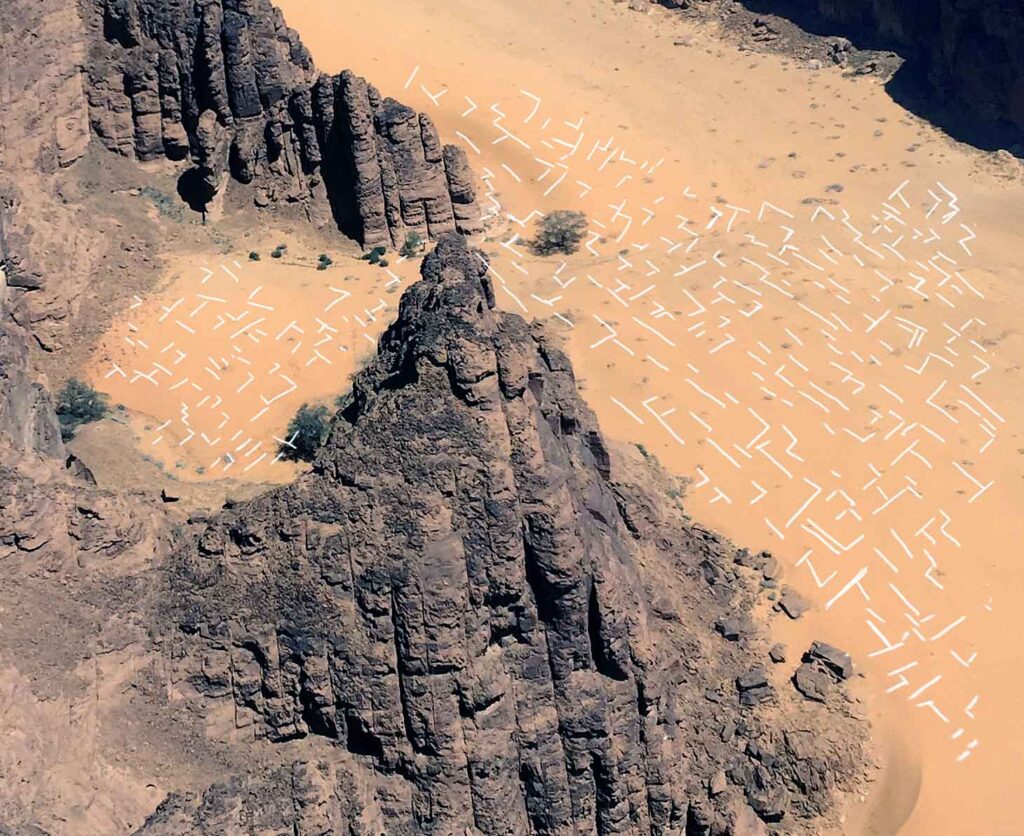

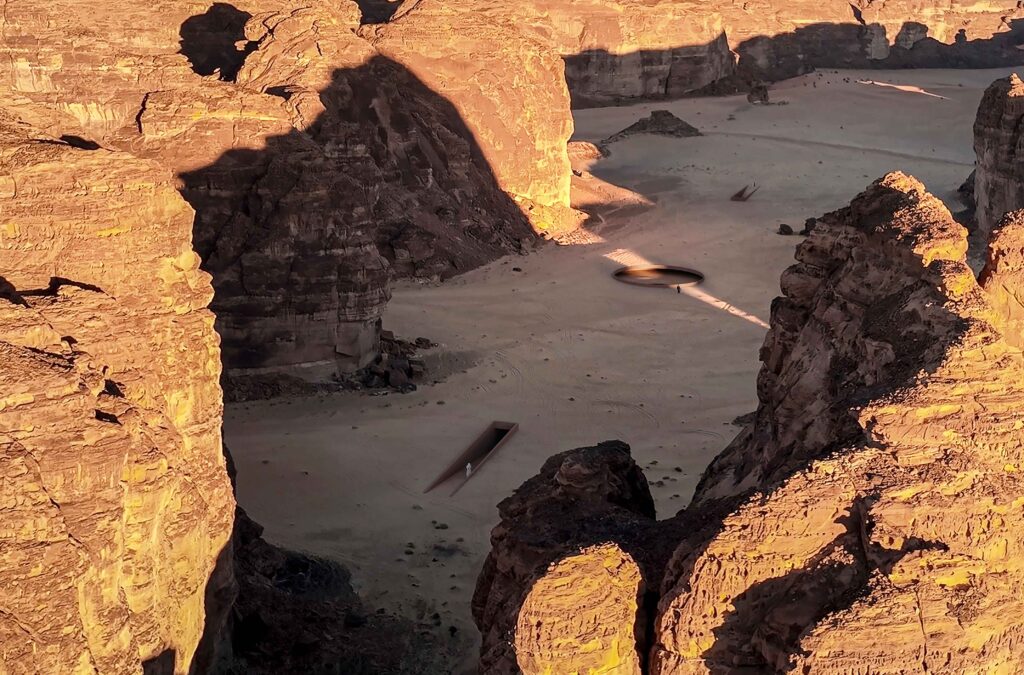

Visualization by Atelier Monolit. Courtesy of ATHR Gallery

Interview

Rajesh Punj: What interests and overwhelms me is the scale of the project that you’ve taken on, and understanding it from your point of view?

Iwona Blazwick: It’s the opportunity to do something almost utopian in the sense that we’re working with a rural community in a pristine landscape where no contemporary art or institution as yet exists. Although of course, AlUla has been impacted by oil, by modernity, the presence of plastics and all that, but nonetheless, it’s a pretty extraordinary opportunity, both in terms of the landscape and the community. Of course we’re not starting from a tabula rasa because there are ancient monuments everywhere and long standing Bedouin, Arabic and Islamic traditions. But contemporary art has been under the radar for decades because of the Wahhabi orthodoxy. And now that the Kingdom is liberalising, it’s a really interesting opportunity to see how art can impact society, and what role we as curators can play in that process; also what we can learn not only from the people but the desert itself. When I joined I was, like everyone else in the world, very aware of the tremendous constraints that Saudi society was under. And now that I’m part of it, part of that community, it’s been very exciting to see how quickly things are evolving, for example, in terms of gender parity, which was my condition for working there, in terms not only of my colleagues, but also of the artists that we’re supporting and commissioning. But equally significant are other new developments, such as the Islamic Biennale, which I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to visit?

RP: Yes, I did. Just before coming to AlUla.

IB: Three things really struck me – first of all the location was symbolic, because it was at the airport for the Hajj, so in other words a site welcoming all those pilgrims coming from around the world. Secondly, the curators brought together incredible artefacts and objects, from both Sunni and Shia cultures. Showing art from Iran, India and Turkey, all these different iterations of Islam, demonstrated a huge signal of openness and toleration; we could revel in the beauty of those visual cultures. Thirdly, the dialogue with contemporary artists that said clearly and not only to people in the kingdom, but to all those visiting the biennale, that contemporary art and Islam are totally compatible. Some of the exhibiting artists are secular, but nonetheless they all responded to the invitation with extraordinary works of art, that created a resonance with that system of belief, and with the cultures that it’s inspired.

The Islamic Biennale has been tremendously important in signalling this huge shift towards an openness, the embrace of other cultures and the possibility of supporting a new language of contemporary art. To be part of that is very exciting. We’re involved in three main arenas. The first is the Wadi AlFann project – we are commissioning land art in 65 square kilometres of the most astonishing desert landscape I’ve ever seen – it’s an intense and wild place. We have been inspired by other outdoor sculpture parks but they tend to be quite restrained, more like outdoor galleries. But this is going to be something else, with works of art in dialogue with the deep time of geology.

Visualization by Atelier Monolit. Courtesy of ATHR Gallery

For artists entering this terrain this is an extraordinary experience; being able to commission in this kind of arena is thrilling because it picks up the land art legacy of the 20th century and brings it into the 21st century. We can see how a contemporary cultural context shapes land art today. The second project is the building of a new museum according to new rules, championing the environment and sustainability, by looking at ancient building techniques, like the wonderful mud settlements of AlUla itself, and seeing if their ancient vernacular techniques and local materials are the key to future sustainability. I was very inspired by this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, which was titled Laboratory of the Future, and I’m shamelessly stealing that to say, could our museum be ‘the laboratory of the future museum?’ Our architect will be Lina Gotmeh who has just unveiled her pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery in London. Our third arena is the great honour of building a collection. We’re acquiring works by artists from the regions adjoining the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea and the eastern Mediterranean, to form a 21st century collection. And so I have the opportunity to research and learn about a region in depth. I have to credit Sultan Sood Al-Qassemi who introduced me to art from the Gulf. In 2015 we presented his Barjeel collection at Whitechapel Gallery through four displays curated by Omar Kholief titled An Imperfect Chronology. That for me was an education, and it offered a foundation for what we’re doing now with this extraordinary project.

AlUla

RP: What interests me when you speak is the notion of time, because it’s about your sowing the seeds for future generations, something that you talked about when we were in the AlUla. I find that fascinating, the responsibility of taking that on, and then delivering something that audiences will see into the future and into many more futures.

IB: Yes all three of these projects are forever! Although for the Wadi AlFann commissions, artists may decide to do something that just dissolves over time, a work that gives itself up to entropy, while others are thinking, if I’m going to make something that’s here in a 100 or even a 1000 years time, what does that mean? How do I approach that? It’s very interesting that we’ve got three great landmark pioneers – Agnes Denes, Michael Heizer and James Turrell; they work with deep geological time and with earth as matter. But younger artists Manal Al Dowayan and Ahmed Mater are adding an element of the societal into their work. Manal is recreating the maze like structure of the old town of AlUla in the desert and inscribing the walls with memories of the people who once lived there, adding their voices to the prehistoric legacies of hieroglyphs, petroglyphs and rock art.

You’re right that it’s all about aspects and understandings of time. With our museum we want to draw on all the knowledge that’s been generated by other initiatives, like Atelier Luma in Arles, or Francis Kere’s Centre for Earth Architecture in Mali for example with their experiments with building materials such as ‘plantcrete’ and rammed earth. There are lots of different initiatives going on around the world, and we are asking whether we can make this building an exemplar of those kinds of ideas? This is something that we in turn would like to share with future museum builders, because our 20th century museums are dreadful in terms of energy consumption – from the way they’re built, to the way they’re operated, to the the way that we make temporary exhibitions. I discovered a great exhibition at the Design Museum, titled Waste Age, I wonder if you saw it? I discovered there that the thing that creates the biggest carbon footprint in exhibition making is the humble screw, because it takes so much energy to create steel screws, yet we use them once and discard them. We need to generate an awareness of our working practices, asking why is everything wrapped in plastic, why is there so much waste? So can we make this museum and the way that we design it, address all those issues, by creating a new paradigm? This is for me the biggest challenge – we may not pull it off, but we’re going to try.

RP: It sounds incredible. One of the things I wanted to ask you, from what I mailed on, is the idea of your beginning again, and what I mean by that is of your deciding what art is and can be? Because it really feels when you talked in AlUla, and from what we say now you, that you are at the vanguard of something new and innovative, and for all of your concerns your beginning with reinventing the wheel if you like, in terms of the works you choose, and the environment you show them in. I am really interested, as I have for some time now, with the notion of what art is, when we see in such a dynamic space and place. So that’s something that, in terms of having asked about time, of space as something that interests me, and the idea of what art is, and what it means – experiential as well as object-based?

IB: Yes we are in the territory of phenomenology, of offering an immersive experience of art. Another challenge is how to broker a relationship with an uninitiated audience. What does it mean to them? How do you begin that dialogue? One way we’ve started is through promoting making – makers learn through their fingertips. So if you have never been used to looking at art but start making, it becomes a way of navigating a relationship with contemporary art. The other challenges is how we prevent it feeling like art is being parachuted in. That’s also important, that everybody feels engaged, and that they feel like it’s for them and about them.

RP: Which l imagine requires a great deal of sitting and talking.

IB: We are finding ways of working with everybody, from the youngest to the oldest. Change can be unsettling, so we have to be very respectful of everyone’s space, their ideas, about what is correct, and what is right for their future. I’m hoping that every interaction we have creates its own opportunity. We’re asking that with the contemporary art commissions artists involve local people, that they mentor someone young or they undertake master classes. We want to make people feel a sense of ownership, that this is not an imposition, but an opportunity. The artist Hassan Hajjaj made a great project in AlUla town this spring; did you see his project?

RP: No, but I am aware of him, having seen his work in Abu Dhabi.

IB: Oh, it’s wonderful. He created an open photographic studio where he took people’s portraits against a backdrop of vividly coloured North African fabrics, having first dressed them from his extensive Moroccan inspired wardrobe. I witnessed a farmer having his photo taken with a baby goat, two generations of the AlUla soccer team, men and women, locals and visitors – it was very cool. I trust artists, who are often very good at mediating and maintaining those relationships.

RP: Another major idea that I asked about is ‘legacy’; I suppose we’ve touched on it already, the idea of future generations. It really interests me, which is possibly why I introduce words like ‘responsibility’ and the ‘future’, of the idea that what you do, has to educate offer art or aesthetics a way of thinking creatively, not just in the class-room but in community spaces; of the dynamic of coming together.

IB: Being creative is a luxury for which you need time. If you’re getting up at four o’clock in the morning for prayers, and you have to tend to your camels, or your harvest, or your kids, or your shop – everyday life for working people, whether they’re rural or urban – to find time to look and to reflect on art is a luxury. We need to make it feel necessary but also beneficial. I’ve become very aware that AlUla is a night-time place because the daytime is just too hot. People come out for their picnics at six and seven o’clock with their families, and then they’re often outside until midnight. So it’s a different rhythm of life and that’s when we need to be able to sit down with people. One of our great ambassadors is Manal AlDowayan because she’s already started having meetings with men and women to talk to them about their memories of AlUla the ancient settlement. She’s been very adept at making people feel listened to and seen, and that’s crucial. It’s a learning situation for us all, a journey that we will all be going on, including you, because you’ve been twice and it’d be interesting for you to judge how it’s progressing.

RP: For me it’s monumental, in my mind the idea that we, and I touched on it already, that art becomes more experiential, and not art in the way that we understand it, and that really intrigues, of re-examining and understanding ‘object-based’ art, that we know of it in Europe, and in the West. What you are invited to do, involved new vocabulary, a new way of seeing with the senses.

IB: I think you’ve touched on something very important, that is a shift in the geopolitical axis of art. Up until the turn of the century, there was a presumption that the west was the sole locus of modern and contemporary art; yet we know there were multiple modernisms and multiple art scenes across the globe that had just never found recognition within the canon or the market – that’s changed irrevocably. And I think that’s been due to some of the great Biennales, like Sao Paolo, Sharjah, Dhaka, Guangjou or Kochi. Now it’s very difficult to say that there is only one centre of art; now there are many. I’m hoping that we can contribute to building an arts ecosystem in Saudi Arabia and the Arab Peninsula – we need art schools, incubator and laboratory spaces, kunsthalles as well as museums; you need the whole system. One of the important initiatives in the Middle East and in Africa is the emergence of artists residencies, and they’re doing really interesting things – in AlUla there is a residency on a farm, where artists are making work in the oasis – I’ve seen incredible work being generated as a consequence of that programme. As we’re edging towards climate catastrophe, I hope we can find ways of coping in a creative way, of bringing hope to a very bleak scenario. So in that way I think it is utopian. It’s also about bringing together artists from different regions, some of which may be in conflict with each other.

AlUla

RP: I see you in a completely new environment, learning more and more.

IB: In relation to everything that I have done in London, this is something else entirely. I mean the idea that you’re not working within an established built environment but in a limitless and boundless place. I had some experience of commissioning art in the landscape with a show of British artists in a National Trust Park in Devon many years ago; and more recently I worked at the High Desert Test Sites in Joshua Tree California. It’s a very different experience than presenting art in the urban public realm. I serve on the Fourth Plinth Advisory Board and the Sculpture in the City project both in London – and here you’re presenting art to an audience of millions surrounded by hundreds of buildings – you know what you’re working with. But in the Saudi desert you’re with camels, snakes and perhaps a Bedouin group might pass you. Of course we are creating these projects both to engage local and regional audiences but also to encourage global cultural tourism. At the same time we are being careful to avoid entertainment or spectacle – our ambition is to stage a profound engagement with some of the greatest art of the 21st century.

RP: It goes back to notions of ‘responsibility’, and of creating something that has real integrity, and that you don’t play to what the underlying expectations are. The legacy is in the sculptural landmarks that you intend for the site, but crucially also in the learning.

IB: Yes, of course; it is about the future.

Read More>> Please Subscribe our Physical Magazine