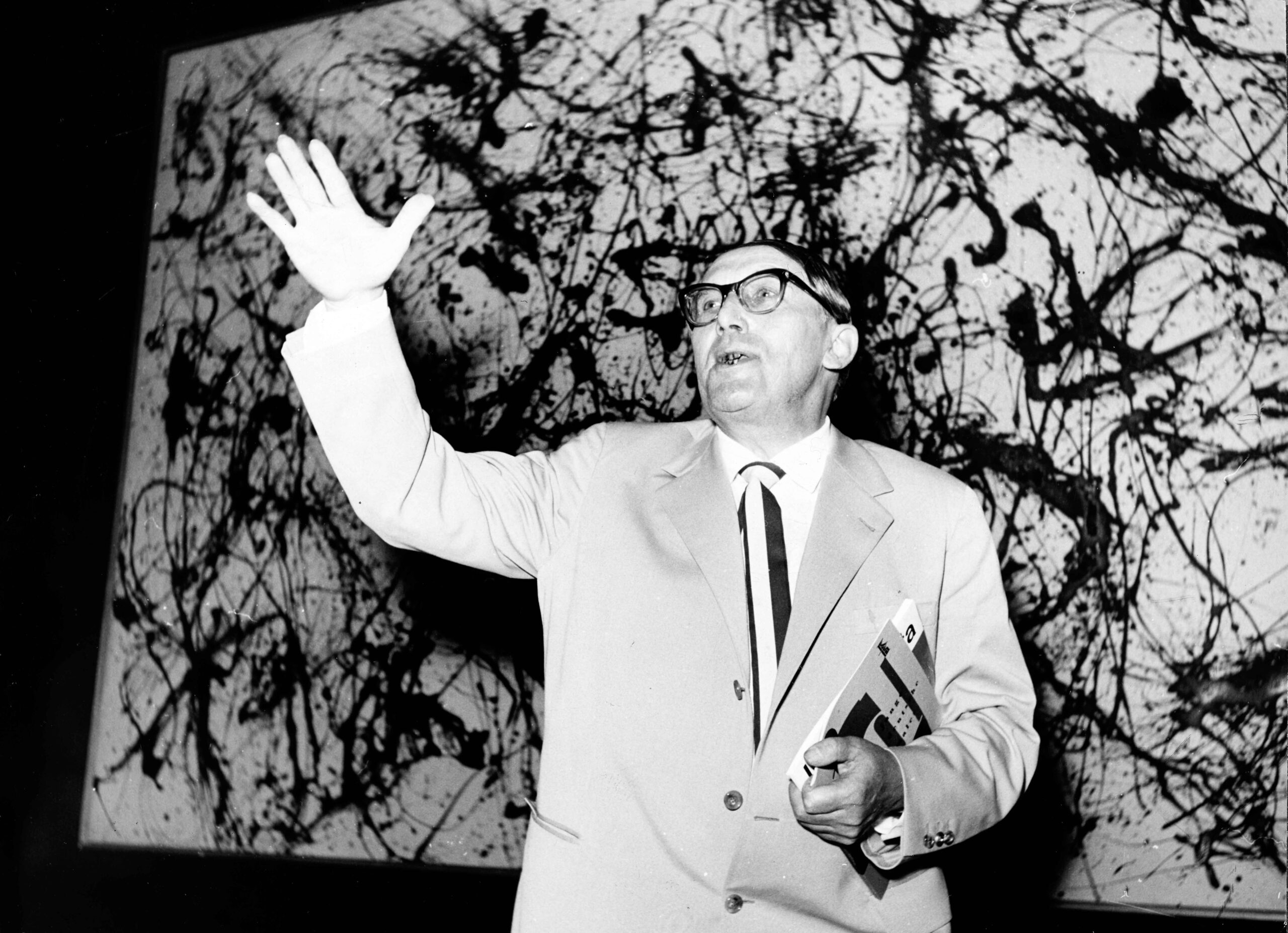

Expressionist Work, Kassel

(Courtesy: documenta archiv, Kassel)

Why is documenta considered to be the most cutting-edge exhibition in the world of contemporary art practices? How was it started and in which direction it is leading? How does it affect the global art practices? We have a number of other significant forums such as Venice Biennale (started in 1895), Havana Biennale (started in 1984), Sharjah Biennale (started in 1993), Gwangju Biennale (started in 1995), etc. What role does documenta play in reflecting upon the new societal changes that we experience and encounter through a stream of images and visuals? The historical trajectory of documenta has reflected the substantial lines of development and tendencies of art in the 20th century.i Also, documenta encompassed the participation of “great masters and defining artists of modernism and contemporary art.”ii How do we apprehend the changes that documenta has mirrored in the purview of globalisation and multiculturalism? It’s always better to trace back documenta from its beginnings and mark out sporadic junctures that accentuate its discourse.

The Beginning

The fact is that the beginning of documenta was under the grip of terror and distress, but there was one man, Arnold Bode (1900-1977), who stood strong to reconstruct the city of Kassel as an ideal city of art like other European cities Paris, Venice, etc. With his relentless efforts a museum from the 18th century was reorganized, which has been known as the Fridericianum, where the first documenta started along with the celebration of a “national garden show” in 1955. The deepening character of documenta embodies a myth and Klaus Siebenhaar, documenta scholar, notes: “No other major cultural event in the world stands in the light of historical momentum as does documenta. Its myth is based on a dialectic of destruction and reconstruction, rupture and continuity in view of dictatorship, world war and cold war.”iii Prior to conceptualizing documenta exhibition, Bode was relentlessly working to make Kassel the centre of art, during the years between the two World Wars, and, in fact; he arranged a show of important German artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Erich Heckel, Willi Baumeister, Otto Herbig, Karl Hofar, Oskar Schlemmer, etc., at Orangerie, a significant architectural site at Kassel, in 1929.iv

The Role of Arnold Bode

The word documenta was coined by Bode himself, which refers to the Latin terms, 1) docere: to teach, instruct, inform, also to show and to tell; 2) means: the intellectual faculties, the mind, and understanding, also used figuratively as soul or spirit of something. Other words such as “documentation” or “to document” and the new meanings can be further implied such as “inventory”, “proof”, “exhibit”, “profess”, “manifest” or “attest”.v The underlying idea of myth is also played out with the portrayal of Kassel, a mid-sized city, which is called documenta Stadt (documenta city). Kassel was essentially a “void city” and considered to be a “blank sheet of paper” in terms of modern and contemporary art.vi

The city was disconnected with modernism as there was no art gallery or museums specialising in modern art. Of late, an art school was re-established. The city of Kassel was destroyed by 80 percent after the devastation of World War II. Arnold Bode’s constant vision for art and culture alleviated the conceptualisation of documenta and eventually, Kassel was totally transformed. Now Kassel stands for “magic city of art” during the months of documenta exhibitions and city life with art.vii After exploring several parts of the city, one would realize that the local population is quite aware of documenta as exhibitions and, by which, they do speak about it with a lot of pride. In a way, the whole city enlivens the staging of documenta. This purports a myth of documenta, by which a local city forges a relationship with the global, from province to the world.viii Truly, this lucidity upholds a highly modern idea, if not necessarily a postmodern one. Nevertheless, Kassel should not be understood as a neutral space rather it is a highly charged ‘political’ space for the discourses of contemporary art. Distinctions have been gauged to stage it differently other than the biennale culture as it is organized every five years with so much deliberation and effort. Also, the selection of artworks does not commence based on national pavilions unlike Venice Biennale and other forums.ix Brigitte Coers, the director of documenta archiv, notes:

“The documenta, as well as other exhibition formats, biennials and collections of contemporary art, are always related to current events, whether as a symbol or seismograph. In my opinion, what is decisive is that the documenta, unlike perhaps other art events, has always succeeded in redesigning, often radically, the conceptual, theoretical and curatorial practices, as well as the process of interaction with the artists, the spatial, urban and scenographic settings. In addition to models of authorial curating, there are discursive counter-projects, as was the case recently with documenta fifteen…. In 1972, Harald Szeemann anticipated the iconic turn and the range of objects of visual culture with documenta 5 and his visual worlds of everyday culture, Okwui Enwezor distributed the Kassel art event with his four Platforms that preceded the 2002 Kassel exhibition at locations beyond western art centers – One constant certainly that documenta provokes, prompts – polemics and contradiction…” x( transl. mine)

The World War II and its Aftermath

After World War II and during the tumultuous period of the Cold War, Germany symbolized the battlefield for a Capitalist—Communist confrontation, there was an oblique desire to display the rewards of West German post-war reconstruction in the face of East Germany which was also the catalyst to the establishment of an international exhibition, documenta, in Kassel, a well-known industrial town, just a few miles away from an installation of international ballistic missiles pointed at the Soviet Union.xi

Besides, the evolution of documenta had to do with a local context based on ruptured German identity in the post-war period, divided between the East having the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the West having the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). While responding to the trauma and damage done by the Third Reich, led by Hitler, the new regime sought through documenta as an event to reconcile German people (volk) and their life with international modernity to transcend/heal from the failure of the enlightenment project because the function of German identity no longer represented a unitary ‘nation’, rather it was caught up in a division.

However, the tussle between socialistand capitalistideologies aggravated, wherein ‘art’ had a specific role to play. This resulted when Clement Greenberg’s assertion of “Modernist Painting” in 1960, a whirl of avant-garde art joined cause with American Cold War politics, which was then focused on the rebuilding of a damaged post-war Europe, itself part of the cause of anti-communism in the United States.xii

The function of the avant-garde was to enhance the totally new and modern Germany; thus, the emergence of documenta was the result of this strategy. In many ways, documenta 1 endeavoured to “mend the broken thread of modernism, reacquainting artists and the General public with the forms of art that had been prohibited during the Nazi era”.xiii In fact, the first two documenta exhibitions (1955 and 1959) were quite Eurocentric in their appeal and a kind of reconstruction of the European art canon of early modernity and early masters of European paintings were represented.

For Arnold Bode and his collaborator, Werner Haftmann (1912-1999), there were clear-cut goals to establish a renewed sense of modernity by showing the modern masterpieces which had been defamed and banned under the Nazi regime and this would strongly sustain the continuity of modernity and the new contemporary post-war art. Also, this kind of project would bring back Germany as a cultural nation in a Western European traditional context and soon embrace the new aesthetic paradigms of abstraction.

Soon, West Germany saw stability due to economic growth which reflected in the German art market too, it was steadily established through the work of exhibitions and galleries, periodicals, and the art press. Also, these were the times when two editions of documenta exhibitions were well received by the audiences. After getting encouraging responses, Arnold Bode established an archive on documenta, which he founded in 1961. Since its inception, documenta archive has been dedicated to the archiving, documentation, and research of modern and contemporary art and its sources.xiv

The notion of novelty and innovation has been inscribed with the staging of each documenta after five years, since 1972, with the selection of an artistic director and afterward a team falls in a place to work on the project. The media reception is quite vital in the journey of documenta therefore “newness” and “newsworthy” is good marketing strategy in documenta editions.xv And so, the persona of the artistic director has been always played to stimulate public attention, as part of its staging.xvi Therefore, a few important canonical editions of documenta would be discussed in this essay which is considered to be defining enactments of documenta, yet stirring the ‘aura’ of respective artistic directors.

documenta 5

Arnold Bode was active till the preparations of the fifth edition which belonged to teamwork. Harald Szeemann, the Swiss art curator was chosen to be the artistic director, the first outsider to design documenta. He was quite theoretical in his curatorial approach. Therefore, the documenta 5 is considered to be the landmark exhibition of the twentieth century. Before documenta, he had already made his name as he curated the most celebrated exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. He presented new awakenings in a new era in the history of the exhibition, challenging prevailing current museum principles and promoting an expanded notion of art. Most importantly, the members of the team that worked with Bode for many years were removed or replaced from the organizational tasks and duties.xvii He aptly made the statement “I am for the classless society, but I must accept that there are at least two: those who have seen my exhibition and those who haven’t. And there is a third one, who hasn’t seen it but talks about it anyway, I don’t know why.” So, most of us belong to the third category because we are only talking about it.

documenta 5 was created together with the team of Jean-Christophe Ammann and Bazon Brock, Szeemann floated for the first time a central theme for the 1972 exhibition, which was titled Questioning Reality—Pictorial Worlds.xviii It is understood that the idea of Szeeman’s teamwork was to examine the criteria that make an object a work of art and to explore the influence of society on how art is perceived. The exhibits consisted of photo-realistic painting, sculpture, ‘happening’, and what were termed as ‘individual mythologies’, the objects from areas of everyday life, such as advertising, political posters, and religious folk art. It is noted that Szeemann’s “event documenta” placed an emphasis on ambiguity and overview, and “critic—information—documentation” were seen as essential fields of curation. It was a matter of “individual mythologies” and a “school of vision” for which Szeemann completely broke with the last conventions of the concept of art. He was regarded as a curator of thematic exhibitions. The application of this notion illustrates that the curator’s idea is more relevant than ever in the debate surrounding the production of exhibitions. Therefore, documenta 5 and the significant role of Szeemann draws so much attention in the art discourses.

documenta 5 was organized at a crucial juncture of social transformations in the late 1960s, whereby the institution of exhibitions was being questioned and bracketed. Szeemann picked up such nuances to play against the institutions of art, providing an alternative to the art market and upholding new utopias. He turned against the traditional approach to presenting artworks in classical fashion to fill the empty spaces.xix

Also, important is the period that conjoins with the interventions of the Frankfurt School and theoretical work, for example, Dialectic of Enlightenment which was entailed by the team of Szeemann. The framework was compiled by the three-part principle “The Reality of Representation, The Reality of Represented, The identity or Non-identity of Representation, and the Represented”xx

documenta X

In the sequence of measuring the trajectory of documenta exhibitions, documenta X is a very significant edition. The selection of Catherine David, a French woman, by the jury, surprised the public to serve as the artistic director. It was the tumultuous period of the 1990s which arrived with layers of so many consequences. David intellectually conceptualized in which more emphasis was given on public dialogues, than only essentializing the works of art as part of discussion. It was the millennium’s last documenta, thus David demonstrated so much concern about the role of contemporary art and cultural practices, she articulates,

in the age of globalization and of the sometimes violent social, economic, and cultural transformations it entails, contemporary artistic practices, condemned for their supposed meaninglessness or “nullity” by the likes of Jean Baudrillard, are in fact a vital source of imagination and symbolic representations whose diversity is reducible to the (near) total economic domination of the real. The stakes here are no less political than aesthetic – at least if one can avoid reinforcing the mounting spectacularization and instrumentalization of “contemporary art” by the culture industry, where art is used for social regulation or indeed control, through the aestheticization of information and forms of debate that paralyze any act of judgment in the immediacy of raw seduction or emotion (what might be called “the Benetton effect”).xxi

Documenta X was highly bracketed by art critics for too much intellectualism, but that was certainly mandatory to frame the contemporary art practices amidst a narcissistic approach that Biennales followed up rather than an altruistic one, what exactly David rendered in the framework. She brought up consciousness of the crisis of contemporary art, “models that are frequently inadequate to the reality of artistic production because they can’t do justice to the extreme heterogeneity of questions and answers.”xxii She broadened the field of culture by expanding vis-à-vis including areas which until recently belonged to anthropology. By keeping the discourse of artistic production in centre she addressed the complex topics of contemporary art “such as physical and geographic, mental and ideological conditions. Questions of sociology, philosophy, and other fields are taken up and articulated in a genuinely artistic manner.”xxiii Documenta X fulfilled an enormous role besides staging an exhibition that usually functions in a classic sense. Since this was considered to be the last documenta of the millennium, it got the institutional character which responded as a kind of “Retrospective” not only meant to look back, but also process historical models and materials to gain insight into the present and look at what lies in the future.

Nevertheless, David exhibited artistic movements since the beginning of the 1960s and began with a chronological survey along the historical axis 1945-1967-1978 and 1989.xxiv This chronological survey ultimately helped her take a fresh look at various socio-political issues, events, and discussions. In a sense, documenta X sharply pitched the theoretical issues of globalization in the field of contemporary art and aesthetics, which were not addressed beyond the purview of social sciences. David reflected upon the historical and critical gaze on its own history, on the recent past of the post-war period, and now on everything from this vanished gaze that remains in ferment within contemporary art and culture memory, historical reflection, decolonization or what she qualified as de-Europeanization of the world.xxv But she is also apprehensive of the new world order that emerged by injecting complex processes of post-archaic, post-traditional, post-national identification (or identities) at work, born after the collapse of communism and brutal imposition of the laws of the free market.

As an inherent asset of documenta X edition, the book Politics/poetics, compiled by David, is the testimony to the tensions and the ideas that situate the artistic productions from 1945 to today, in their political, economic, and cultural context of appearance and in the light of the multiple shifts and redefinitions that have now become manifest with the process of Globalization.xxvi It is argued that documenta 11 of Okwui Enwezor took up a number of these same questions and elaborated them further. xxvii The question of decolonization and the problem of postcolonial theories were already set forth in documenta X by Catherine David. So, documenta X has been lauded as the preparatory documenta.

documenta 11

How do we read documenta 11 in terms of politics? By which means, how does the curatorial notion of documenta 11 function do and conceive a vision of diversified postcolonial art? Does this vision (based on Okwui Enwezor’s ‘Global Postcolonial model’) sustain the specific model (of art and culture) reflective of the abolition of colonialism and the process of decolonization?

Enwezor is neatly making a theoretical argument in the catalogue where he pushes the postcolonial assumptions into the view of globalization or the global system. He says,

“From the moment the postcolonial enters into the space/time of global calculations and the effects they impose on modern subjectivity, we are confronted not only with the asymmetry and limitations of globalism’s materialist assumptions but also with the terrible nearness of distant places that global logic sought to abolish and bring into one domain of deterritorialized rule. Rather than vast distances and unfamiliar places, strange peoples, and cultures, postcoloniality embodies the spectacular mediation and representation of nearness as the dominant mode of understanding the present condition of globalization. Postcoloniality, in its demand for full inclusion within the global system and by contesting existing epistemological structures, shatters the narrow focus of Western global optics and fixes its gaze on the wider sphere of the new political, social, and cultural relations that emerged after World War II. The postcolonial today is a world of proximities. It is a world of nearness, not elsewhere. Neither is it a vulgar state of endless contestations and anomie, chaos, and unsustainability, but rather the very space where the tensions that govern all ethical relationships between citizen and subject converge. The postcolonial space is the site where experimental cultures emerge to articulate modalities that define the new meaning and memory-making systems of late modernity.”xxviii

The curators of the same exhibition have made a distinct argument in a recent interview with the documenta archive, “Documenta11 was seen or referred to as a global exhibition but there were lots of white spots because it wasn’t set up, it didn’t intend to be global. And the question that comes in now is not just of the post-colonial constellation but also of the post-Cold War (Mark Nash).”xxix

In essence, documenta 11 was proposed in the form of a conference conjoining with the structure of art, politics, and society in a postcolonial as well as global world. A network of global venues was being arranged to chart out Platforms from 1 to 5 (Platform1: Democracy Unrealized (Vienna and Berlin); Platform 2: Experiments with Truth: Transitional Justice and the Processes of Truth and Reconciliation (New Delhi); Platform 3: Créolité and Creolization (Saint Lucia, Caribbean); Platform 4: Under Siege: Four African Cities, Freetown, Johannesburg, Kinshasa, Lagos (Nigeria); Platform 5: Documenta11 (Exhibition at Kassel). Platform 5 encompassed all the ideas and movements that had been previously discussed, arrived, and brought to exchange. For Enwezor, Documenta (Kassel) was a connecting space and “transitional place of artistic-intellectual” exchange for continents.xxx With such a framework Enwezor pushed further the idea of discursivity and fatefulness.

Yet, there is another Platform which is virtually being formed by the documenta archiv where Enwezor’s team members and his collaborators are facilitated to expand the discourse of documenta 11. It is known as Platform 6 which establishes how discourses that emanated from documenta 11 and its platforms shaped up and always manoeuvred the trailblazing curatorial discourses in wide-ranging capacities. The whole idea is to look upon the means of how documenta 11 as local exhibition spaces in Kassel coalesce with the global while coinciding with the political, social, and cultural spaces.

Rasheed Araeen, a renowned art historian and artist, strongly condemns Enwezor for his experiments in mounting documenta 11. Further, he shows disagreement with the use of the term postcolonialism and adherence to the notion of multiculturalism.xxxi For Araeen, there are more efforts to be taken from the Western dominant order and the theoreticians from the colonized subjects to recognise the achievement of postcolonial discourse in exposing and confronting these structures, as a result of which there is greater awareness of equal rights for all people all over the world. He says, “the demand of these people for recognition of their self-representation has in fact led to what we today call multiculturalism or recognising, that the world comprises many cultures whose diversity must be acknowledged and protected, both in places of their origins and where they have migrated to.”xxxii He remarks blatantly that the failure of institutionalised postcolonial discourse was on display in the documenta 11.xxxiii There was “disturbing dichotomy” between what was being articulated in the Enwezor’s claims and what was displayed, mentioned further by Araeenxxxiv

Conclusion

There is no doubt that documenta 11 is legitimately considered to be the first postcolonial documenta and this edition calls into question of tacit “attention hierarchies” of the Western exhibition world.xxxv It also brackets the legitimacy of the West’s exoticizing view of the “foreign” which is quite apparent in the earlier practices of art in the wake of modernism. More or less, the three editions of documenta led by Szeemann, David, and Enwezor have set out new measures stimulated by radical models for the documenta. The experiments entailed by these distinct artistic directors have paved the way for successive documenta exhibitions, namely documenta 13, documenta 14, and documenta 15. documenta13 was directed by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. Caught up by the theme of globalization, multiculturalism, and postcolonialism, these editions have indirectly or indirectly entangled in the web of theoretical implications designed in the early editions of documenta which mentioned early at length.

Taking the concept of platforms from documenta 11 a step further, documenta 13 included not only events outside the city of Kassel in advance of the exhibition but also a concurrent event at a different location, for instance, the former Benedictine Monastery in Breitenau outside Kassel and Bamiyan, Kabul.

Documenta 14 directed by Adam Szymczyk. An intriguing notion of ‘education’ was floated to build projects with schools, universities, art colleges, and communities relating specifically to documenta 14 artist projects. The program of an education was to reach a wide and diverse audience that is open to thinking about the social role of art and artists in today’s society. The project was also hosted in Athens besides Kassel.

The ideas of multiculturalism, globalization, and localization have been entrenched in the last three editions of documenta. For instance, documenta fifteen is more apparent in dealing with ‘local’ to ‘global’, by defining the term Lumbung, which traditionally has been used in Indonesian provinces for “community’s harvest”. In documenta fifteen, it was rendered as a curatorial method to forge networks or “connectivity” with various layers of art and community across the world, from the site of Kassel. In the next part, I would like to take examples from the most crucial artworks exhibited in the debated editions of documenta, for upholding this discourse. Also, one could establish a kind of connection with how some of the canonical artworks/exhibitions in the “staging” of documenta tend to produce art history.xxxvi

Documenta is a strange affair. Critics echo that “documenta is imbued with a kind of weirdness that is lacking in other, more buttoned-up biennials.”xxxvii It is so because it carries so much mystery around an artists’ list and the team members always drop just days before the show opens. It is more experimental than any other global exhibition in the world. If it can shock its own brainchild, Arnold Bode during the staging of documenta 5, it can shock anybody, whether the “insider” within documenta administration or the “outsider,” just by its mythical trial and strange state of affairs!

(I would like to extend my acknowledgment to the documenta archive and all the colleagues for helping me with their in-depth insights and allowing me to use treasured images.)

Endnotes

I. Klaus Siebenhaar, “Preface”, documenta: a brief history of an exhibition and its contexts, Siebenhaar Verlag, Berlin and Kassel, 2017, p.7.

ii. Ibid. 7-8.

iii. Klaus Siebenhaar, The Myth of Documenta: Arnold Bode and His Heirs, Central of Fine Arts, Beijing and Frei Universitaet, Institut für Kultur-und Medienmanagement, Berlin, 2017.

iv. The “4. Big Art Exhibition Kassel”, committed to the topic “New Art”, is open in the Orangery. Some artists convey a „new view of the industry “.https://www.kassel.de/buerger/stadtgeschichte/chronik/inhaltsseiten/chronik-der-jahre-1900-1944.php (accessed on 10 August 2023). also

v. Christoph Lange, The Spirit of Documenta: Art Philosophical Reflections, in archive in motion: documenta manual, Gottingen: Steidl Verlag, 2005, 14 and Klaus Siebenhaar, op.cit. 15-16; The future exhibition was given the name “documenta”. This is said to have been an idea of Ernst Schuh, a friend and colleague of Bode at the Kassel Academy. From “documentum” came “documenta”—similar to “constructa”, “correcta” or “abstracta”. However, Ernst Schuh had to hand over his idea to Bode. Arnold Bode will henceforth refer to himself as the creator of the name. Kroth wrote: “Ernst Schuh, lecturer in painting techniques at the Werkakademie and close associate of Bode’s team for the first documenta, had the brilliant idea at the right time: “documenta”. He had to sign that he would not use it and that this name was only available for this exhibition.” (transl. mine), R Kroth, in: Orth, 2007, 24, von Sylvia Stöbe, Arnold Bode: Künstler und Visionär Begründet der documenta eine Biograofie, Eurogio Verlag, Kassel, 2021, 52.

vi. Klaus Siebenhaar, op.cit., 15.

vii. Ibid., 15-16.

viii. Harald Kimpel, “Warum gerade Kassel? Oder wie wird Kunstgeschichte gemacht?” in Mythos Documenta: Ein Bilderbuch Zur Kunsrgeschichte: Kunstforum International, bd 49, 3/82, Apr/Mai, 22-33.

ix. It was started to showcase the European development and entanglements after the World War II but later documenta exhibitions shaped up on its own, caught up by new insights from the artistic directors in each edition respectively see Franziska Voelz, “Biennale Venedig und documenta-versteckte Beziehungen? Zu Konzepten, Kuenstlern und Organisatoren,” in Beziehungsanalysen Bildene Kuenste in Westdeutschland nach 1945, Wiesbaden: Springer Vs, 2015, 229-256.

x. “Eine Konstante liegt sicher darin, dass die documenta provoziert, zu Polemiken und Widerspruch herausfordert: Ein Interview mit Birgitta Coers Leiterin des documenta archiv von Peter Funken” in Kunstforum International, Band 287, Post-Vandismus Issue. Online version https://www.kunstforum.de/artikel/eine-konstante-liegt-sicher-darin-dass-die-documenta-provoziert-zu-polemiken-und-widerspruch-herausfordert/ (accessed 17 August, 2023).

xi. See. Art Since 1900: modernism, antimodernism, postmodernism, Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloch (eds.), 424.

xii. Marxist art historians have argued that influential exhibitions of US art in Europe in the 1950s and 60s were quietly supported by the CIA, through an organisation called, in wonderfully Cold War style, the Congress for Cultural Freedom. During the 1950s, American art overtook European Avant-garde and crushed Communism. This was one Cold War weapon to which the Russians had no answer. Stalin’s doctrine of “Socialist Realism” demanded good, honest art that people could understand. But Communism was defeated in the Cold War at least in the domain of Art. See. Jonathan John,“A Giant Awakes” in The Guardian (online version) http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/sep/18/art.coldwar and Frances S Saunders, “Modern Art a CIA weapon” in The Independent,(online version)http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/modern-art-was-cia-weapon-1578808.html (accessed June 2013).

xiii. Keren Lang, “Expressionism in Two Germanys,” in Art of Germanys: Cold War Cultures, Sabine Ecknmann and Stephanie Barron (eds.), Abrahms & LACMA, p. 90. Cited Sean Rainbard, “Past Battles, Distant Echoes,” in German Art Now, 25.

xiv. The focus of documenta archive is on the documenta exhibitions since 1955, curatorial practices and documentary strategies. There are numerous publications that have carried on various aspects of documenta and other international perspectives. documenta archiv is an autonomous body which works in collaboration with documenta Fridericianum and documenta institute, Kassel. https://www.documenta-archiv.de/en/information/2604/about#2606/history (accessed on 11-08-2023)

xv. Nanne Buurmann and Dorothee Richter, “documenta: Curating the History of Present,” in On Curating, issue 33/June 2017, 4.

xvi. Ibid., 4.

xvii. “Brock and Szeemann embodied this change in completely different ways. Szeemann, fascinated by their art through many years of exhibition practice and constant contact with artists, articulating himself without a social mandate but also without consideration, had discovered the artistic aspects of his ability to communicate and brought them, half art historian, half saint, now also applies to his working methods after his exhibition When Attitudes Become Form had shown that not only artists, but also art mediators can become stars.” (transl. mine), Walter Grasskamp, “Modell documenta oder wie wird Kunstgeschichte gemacht?” In Kunstforum (Mythos Documenta), band 49, 3/82, April/ Mai, 1982, 21-22.

xviii. Documenta: Politics and Art, Deutsches Historisches Museum, Prestel 2021, 145.

xix. Gabriele Macker, “At Home in Contradiction: Harald Szeemann’s Documenta,” in archive in motion: documenta manual, Göttingen: Steidl, 253-254.

xx. Ibid. 255.

xxi. Catherine David, “Introduction” documenta X: Short guide, Cantz, 1997.

xxii. Bettina Steinbruegge, “Documenta X: An Anthology of the Present,” in archive in motion: documenta Manual, Michael Glasmeier, Karin Stengel (hg.), Gottingen: Steidl, 2005, 354.

xxiii. Ibid. 353.

xxiv. Ibid. 353.

xxv. Catherine David, “Introduction” documenta X: Short guide, Cantz, 1997.

xxvi. Ibid.

xxvii. Bettina Steinbruegge, “Documenta X: An Anthology of the Present,” in archive in motion: documenta Manual, Michael Glasmeier, Karin Stengel (hg.), Gottingen: Steidl, 2005, 354

xxviii. Okwui Enwezor, “The Black Box” in Documenta 11_Platform 5: Exhibition (Catalogue), Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2002, 44.

xxix. Besides Okwui Enwezor, who was artistic director of documenta 11, the co-curators were chosen to work in the team such Octavio Zaya, Sarat Maharaj, Susane Ghez, Carlos Basualdo, Uta Meta Bauer and Mark Nesh. https://www.documenta-platform6.de/wp-content/uploads/talk1-part1_the-past-in-the-present.pdf (accessed on 10-08-2023)

xxx. Klaus Siebenhaar, documenta: a brief history of an exhibition and its contexts, Siebenhaar Verlag, Berlin and Kassel, 2017, p.57.

xxxi. Rasheed Araeen, “Eurocentricity, Canonization of the White/European Subject in Art History, and the Marginalization of the other” in Globaliesirung/Hierarchisierung: Kulturelle Dominanzen in Kunst und Kunstgeschichte, Irene Below und Beatrice von Bismarck (eds.), Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 2005, 54-55.

xxxii. Ibid. 55.

xxxiii. Ibid 55.

xxxiv. See Araeen, op.cit. (2005), 55.

xxxv. Wolfgang Lenk, “The First Postcolonial Documenta,” in archive in motion: documenta Manual, Michael Glasmeier, Karin Stengel (hg.), Gottingen: Steidl, 2005, 375.

xxxvi. Nanne Buurmann and Dorothee Richter, “documenta: Curating the History of Present,” in On Curating, issue 33/June 2017, 2 and Walter Grasskamp, “For Example, Documenta, Or, How Is Art History Produced?” in Thinking About Exhibitions, Reesa Greenberg, Bruce Ferguson and Sandy Nairne (eds.), London and New York: Routledge, 1996, 48-57.

xxxvii. Alex Greenberger, “Why the Art World Descends on a Small German City Once Every Five Years,” in Artnet News, June 16, 2022https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/what-is-documenta-why-is-it-important-1234631856/ (accessed on 11-08-2023)

Rahul Dev (Goethe Institute Research Fellow, documenta archiv, Kassel)

Read More>> Please Subscribe our Physical Magazine