Matters of he ART With Paramjot Walia

Saba Hasan

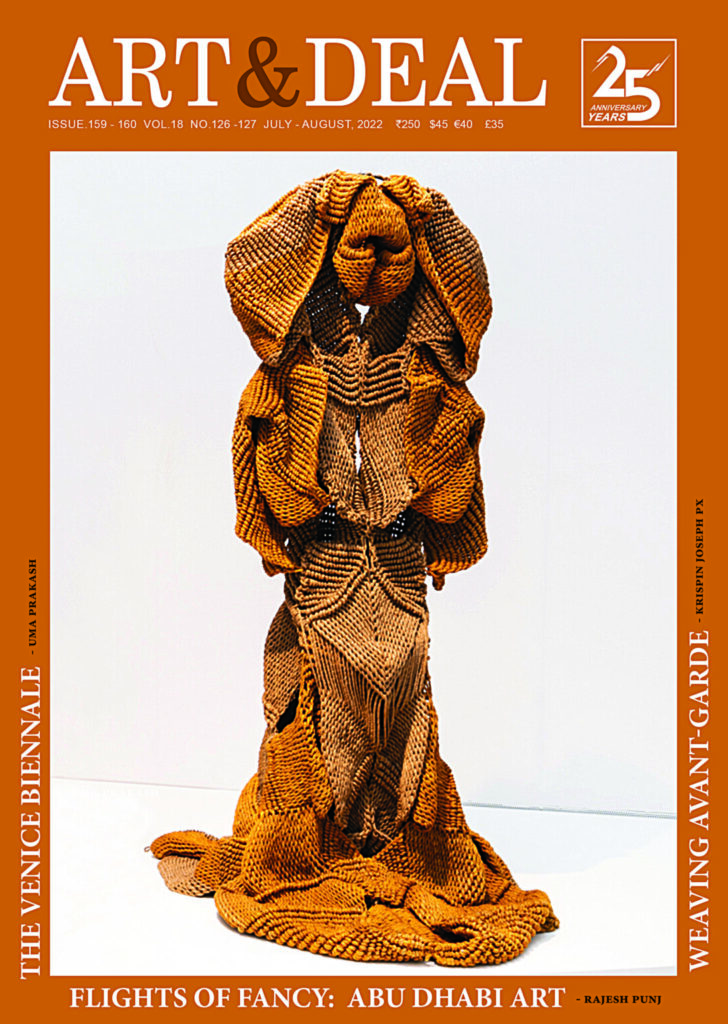

Saba Hasan, a Delhi based artist, has been awarded international fellowships from Syracuse University, New York,the French Cultural Ministry, Paris, the George Keyt Art Foundation, Colombo, the Oscar Kokoschka Academy in Austria, 2010 and the Raza National Award for painting in 2005.The versatile artist also exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2013 as part of the Imago Mundi Collection. Apart from her mixed media works which are both abstract and conceptual, her installations, videos and photographs explore new dimensions and possibilities. Saba uses unconventional mediums to create a pictorial space where reality is hammered, scratched, burnt but finally liberated. Paramjot Walia tries to find the artist in the labyrinth of healed spaces through the conversation.

Art&Deal : How would you describe yourself as an artist?

Saba Hasan : Privileged, I think, for I was always generously given the love and freedom to be who I am. I experiment a lot and have been working across media for many years.As an artist I work with a singularity of purpose, when I am at my station nothing can distract me. My relief paintings came out of this obsessive exploration in the studio tackling the surface without using conventional paints. Through years of focus I have devised a visual vocabulary, which crosses over into all the media I work with. I have never felt disadvantaged or confused in terms of my artistic expression since the age of three, when Aunty Gauba gave me a brush to paint the wall of our nursery school.The doubts that come arise once I plunge my self into work and are related to the process itself. The resolution may take time but the pleasure of not knowing is as thrilling as certitude for me. I inevitably challenge myself with a new material, idea or medium to disturb my complacent practiced old hand.

AD: In some of your works Islamic texts are seen. Does it in any way speak of a religious protest?

SH: No, Urdu, is not a religious but an indigenous cultural symbol of plurality in my work. Traditionally with the Bible and the Koran, the written word took connotations of each religion and texts were to be revered, as they were the words of God but these are different times. I have collaged extracts from Mahashveta Devi in Urdu, poetry, letters to me, to bring in a variety of contemporary voices from our world. When I write my sound works in English I can hear echoes from Urdu but they carry within a desire to belong to many worlds, a paradox of connections between places I have lived in like Russia, India, America, Switzerland, France. From Tagore as much as from Pushkin or Hafiz to Lorca, I have now learnt to speak in a voice invoking many myths.

AD: In one series you have used the letters from your mother. Please elaborate for our readers.

SH: In my series titled, “Letters from Baton Rouge”, I used text from letters written to me by my mother. These letters being her personal accounts, bring into the frame warmth and authenticity. Admissions of loneliness, love, humour, political criticism are all bare to see and allow allusions to be intimately shared. All the other materials like sand, soot, nails and rope continue to enrich my grammar and with leaves, sea weed, shells, and forest debris now bringing in the natural, more organic dimension into my art making. This is a connection with my mother, my mother tongue, as well as a metaphor for mother earth.

AD: Along with burning ,slashing and hammering of nails on canvas there is also stitching in your works. In a way there is both resistance and rebellion. Please Elaborate.

SH: Around 2002, the focus in my work shifted from paints to materials like fabrics, paper, ropes, cement, nails and burnt text, gradually building a visual alphabet encompassing a variety of acts and emotions.This was to me a chance to occupy several worlds. To be in the middle of the chaos, to bristle, to renunciate and to do it where it is most vulnerable to lyricism I tie up books, lock them away, fossilize, cut them, burn them and some embalmed for posterity. The intention is to raise doubts about what is considered to be the absolute truth. There is protest and rebellion in all my works, a quiet subversion. It is important to know however that in the conflict there is a moment of stillness, which I usually choose as the resolution for my work be it sound, video or painting.

AD: Your work reflects socio-political objectivity or is simply defined by emotions and spontaneity?

SH: I don’t want my works to be looked at with preconceived ideas but in the light of ambivalence. The content of my work is such that I can be said to walk the line between the real and the imagined. I try to express the complexity of our condition but in an allusive way. To give an example, my video “Haqeeqat or The Truth Project”, a part of the Sarai Reader Exhibition 09 explores the philosophical, ethical and political perspectives associated with the notions of truth. Here I pose a set of questions like, who is to determine what is right or wrong? Is what we perceive as the truth, the only truth or is it a falsehood from another point of view? Is there a danger that the truth can subvert our good intention and compromise our future rights? Art for me, like life, is about that space where I decide what I really stand for and that is a political act every hour of the day.

AD: Is your work creation process a way to purge away past?

SH: Maybe, I have not thought of it that way but now that you mention it burning, stitching, wrapping, fossilizing, embalming all my techniques of treating my material have an end of time element to them. Death and mortality have been concerns in my abstract works, in fact I had a show of mixed media paintings, called “Of Goats and Graves”in 2007 around this very idea. My father had told me how a grave is meant to be unassuming and however grand your life, once beneath the mound, let go and make way for others, my first lesson in mortality.And so it is, my parents’ graves are thick with grass shaded by kikar trees but without a headstone. I went once to place flowers there and a brood of eager goats living in the graveyard rushed to devour the petals. Initial anger gave way to laughter; the goats finally drove the point in, as if through an art performance. Mortality ensures a purging of the past.

AD: Tell us something about your current project.

SH: An important preoccupation as part of my practice, continue to be the walks in Hauz Khas park. I have built a large body of photographs tracing these walks and created a soundscape of my route, aired on Osso Radio, Portugal. My new works are related to them and are for wandering spirits. The collection comprises my video poems, called “four haikus” and photographs. Here I want to evoke an age of innocence that has since been lost in contemporary art and to show our closely entwined lives with nature.My current works instill the power of direct experience, which is critical to my oeuvre. Each moment is a seized one and pictured in its purity of color and light. My walking, listening to music, crouching on the muddy banks with my camera, living for days on the boat, all become contingent to the photograph. I insist often on noting the time of the day or place, as in a haiku, the poet marks the season.

AD: Last question…What keeps Saba Hasan going in tough

times?

SH: Without a doubt, my family, my dog, music, friends and

a trip to Goa.